Blaxploitation Education: Hell Up in Harlem

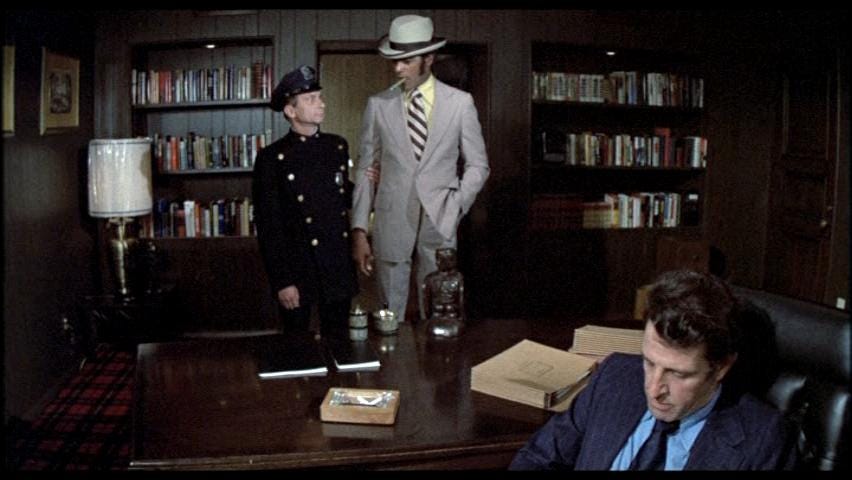

Fred Williamson comes back from the dead for more gangster action.

Hell Up in Harlem

Written and directed by Larry Cohen

1973

Blaxploitation sequels tended to be less than satisfying, but that’s true of sequels in general, which often fail to recapture the magic that enthralled viewers the first time around. The impulse to make these sequels is obvious, especially when movies feature characters who are so charismatic that people can’t get enough of them. However, Black Caesar is an odd choice in that respect, not only because its main character was less than heroic, but also because he apparently died at the end of the film. Hell Up in Harlem doesn’t even have the excuse of being made by different filmmakers. As with the original, it’s written and directed by Larry Cohen, who apparently didn’t have the foresight to end the first movie in a more open-ended fashion, even though he must have gone right into making the sequel, given that it came out less than a year later.

Whatever the reasoning may have been, Cohen spends the opening of the sequel undoing the ending of the first film, revealing that no, Tommy Gibbs (Fred Williamson) didn’t die alone and unmourned; instead, his father (Julius Harris) came to rescue him and get some of Tommy’s associates to take him to a hospital in Harlem. Papa Gibbs (as he’s referred to throughout the film) also hides the ledgers that Tommy had been using as leverage against other figures in New York’s underworld, and Tommy instructs him to call up the district attorney and threaten to release incriminating information if he doesn’t tell the cops to let Tommy go after receiving treatment.

This all serves as a retcon, since the reason Tommy had “died” in the first place was because he no longer had anybody on his side. If he had a squad of “brothers” ready to back him up, surely he would have gotten them to help him earlier. But that doesn’t really matter, because this movie is about Tommy re-establishing himself at the top of the New York organized crime scene, so most of his past sins have been forgotten so that audiences will actually be on his side this time around.

In another change of character, he decides to make his father an integral part of his operations. Even though he almost killed Papa Gibbs in the last movie for deserting Tommy and his mom when he was a child, he’s now happy to have his dad join his criminal efforts. What’s more, Papa Gibbs, who previously seemed to be somewhat ashamed of his son, is now excited to be a big-time player, reveling in his newfound power and directing hits against everyone who might impede their operations.

Tommy’s schemes mostly consist of taking out as many of the existing players in the mafia as possible, including a scheme in which he and his men sneak onto an island off the Florida keys where several kingpins are vacationing, kill all their goons, and taking them hostage until they agree to Tommy’s terms, which I guess are just to let him be the big boss of New York. This is a pretty fun scene, starting with Tommy and his compatriots snorkeling as they sneak onto the island, which gives him a chance to quip that white people were wrong when they said Black people can’t swim. In the ensuing shootout, a couple Black women who had served as servants pull out guns and shoot some of the mafia guys, with big smiles on their faces as they get to turn the tables on these white assholes. At one point, one of the bikini babes who had been frolicking in a pool fights back using some kung fu moves, and Fred Williamson (or his stunt double) roundhouse kicks her in the face. Later, when Tommy is holding the bosses hostage, he has the women serve them soul food just so he can enjoy their distaste at having to eat it (a better joke would have been if they had thought it was delicious, but oh well, I’m 50 years too late to do any script doctoring).

After returning to New York, Tommy is back on top, and like in the first movie, he pays lip service to being the kind of kingpin who supports the Black community. However, this mostly consists of him stopping shipments of heroin into the city, both as a way to prevent the mafia from earning money but also because he says it’s destroying his people’s neighborhoods. How exactly his criminal enterprise makes money is never explained, but that’s also in keeping with the first movie, which seemed to assume that being a gangster just involves killing your enemies and then being rich.

The only other way the movie really approaches social commentary comes when Tommy reconnects with his childhood buddy Rufus (D’Urville Martin), who has completely given up a life of crime in order to focus on his ministry as a preacher. We see that Rufus has become famous and regularly appears on TV to give sermons where he condemns Tommy’s criminal activities. When Tommy confronts Rufus about this, he complains that the only reason white people allow him to be on TV is because he furthers the narrative of Black-on-Black violence rather than talking about the actual issues affecting Black people. That’s some pretty incisive commentary for a movie that came out in 1973, and it’s still pretty relevant today. Unfortunately, that’s about it for anything about race in this movie, which mostly just focuses on Tommy’s life of crime.

While Tommy’s character has been toned down a bit from the first movie, he still does some stuff that’s pretty bad. Specifically, he decides that his old girlfriend Helen (Gloria Hendry) had betrayed him, so he takes her children away from her. Never mind that the reason she took those actions against him was that he had engaged in horrific sexual and physical abuse against her. It seems like we’re supposed to be on his side as he torments her, refusing to allow her to see her children but also preventing anyone else in the world of organized crime from doing anything against her, all so she can continue to live a miserable existence and be denied any happiness.

We don’t really get to see Tommy receive any comeuppance for this behavior though, because somebody decides to kill Helen anyway in defiance of his orders, all as part of a power grab. This would be a new character named Zach (Tony King, who was in Gordon’s War and Shaft), who starts out as one of Tommy’s men but soon starts secretly working for DiAngelo (Gerald Gordon), the D.A. who serves as the main antagonist here. His killing of Helen is meant to drive a wedge between Tommy and Papa Gibbs, who DiAngelo tries to frame for the murder, but all it does is make Tommy decide to get out of the organized crime life altogether and move to Los Angeles with his new wife Jennifer (Margaret Avery, who was in Cool Breeze but is probably best known for her Oscar-nominated role in The Color Purple), along with Helen’s kids, who he has adopted as his own.

In Tommy’s absence, DiAngelo and Zach reassume control of organized crime in New York, which is mostly done by Zach confronting Papa Gibbs, who is so pissed off that he challenges him to a fistfight. This seems like a poor decision, given what must be at least a 20-year age gap between them. While the fight is surprisingly even, Zach prevails after Papa Gibbs’ heart apparently gives out, causing him to die and leaving the city wide open for a takeover.

As so often happens in these types of movies, the antagonists (you can’t really call them the bad guys, since everyone here is pretty bad) can’t be satisfied with their success while Tommy is still alive, so they send a bunch of men to kill him. He manages to defeat them all, of course, and now he’s out for revenge. In fact, he turns it into a revenge tour of New York, doing things like climbing up one of the big billboards in Times Square to shoot someone with a sniper rifle, going to Coney Island and stabbing a sunbathing mafia don with a beach umbrella, and gunning down a bunch of guys in front of a hot dog stand, even leaving one of them dead on the ground with a hot dog protruding out of his mouth.

This is all enjoyable enough, and it leads to a cross-country chase in which Tommy pursues Zach back to L.A., arriving just in time to have a big fight in the airport’s baggage claim, then has to go rescue his son, who is being held hostage by DiAngelo. The action seems to be the real focus in this movie, with plenty of exciting shootouts and gangland assassinations. Any flaws in Tommy’s character are mostly holdovers from the first movie, and by the end, he has morphed into an action hero that audiences are meant to cheer for wholeheartedly.

If you can ignore the disconnect between Black Caesar and Hell Up in Harlem, the latter is pretty fun, with Fred Williamson dialing back the aggressive and abrasive aspects of his character and being a much more straightforward protagonist. Larry Cohen gets to throw in some artsiness, such as in a scene where Papa Gibbs and his men are beating up some Japanese gangsters who had been trying to bring drugs into the city, and part of the scene is shot with a camera providing street-level view half a block away, letting us view the action through the steam rising from a manhole. And while we don’t get a James Brown soundtrack this time around, he’s replaced by Edwin Starr, who contributes several good songs, including “Ain’t it Hell Up in Harlem” and “Big Papa.” All in all, it’s a pretty good time, and it’s too bad it’s Cohen’s last swing at the Blaxploitation genre.

Blaxploitation Education index:

UpTight

Cotton Comes to Harlem

Watermelon Man

The Big Doll House

Shaft

Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song

Super Fly

Buck and the Preacher

Blacula

Cool Breeze

Melinda

Slaughter

Hammer

Trouble Man

Hit Man

Black Gunn

Bone

Top of the Heap

Across 110th Street

The Legend of N***** Charley

Don’t Play Us Cheap

Shaft’s Big Score!

Non-Blaxploitation: Sounder and Lady Sings the Blues

Trick Baby

The Harder They Come

Black Mama, White Mama

Black Caesar

The Mack

Book of Numbers

Charley One-Eye

Ganja & Hess

Savage!

Coffy

Shaft in Africa

Super Fly T.N.T.

Scream Blacula Scream

Cleopatra Jones

Terminal Island

Gordon’s War

Slaughter’s Big Rip-Off!

Detroit 9000

Hit!

The Spook Who Sat by the Door

The Slams

Five on the Black Hand Side

The Black 6

James Brown was all set to score "Harlem" originally, but the filmmakers made the atrocious mistake of telling them his planned music was "not funky enough", which naturally made him blow his stack. (The music in question was "The Payback", which would become one of his many great hits). Instead, two Motown veterans- writer/producer Freddie Perren and singer Edwin Starr- ending up handling the tune work, which carries its own funky grooves.

I love this movie, and it should be the template for every sequel after the guy died at the end of the first one.

Fromtheyardtothearthouse.substack.com