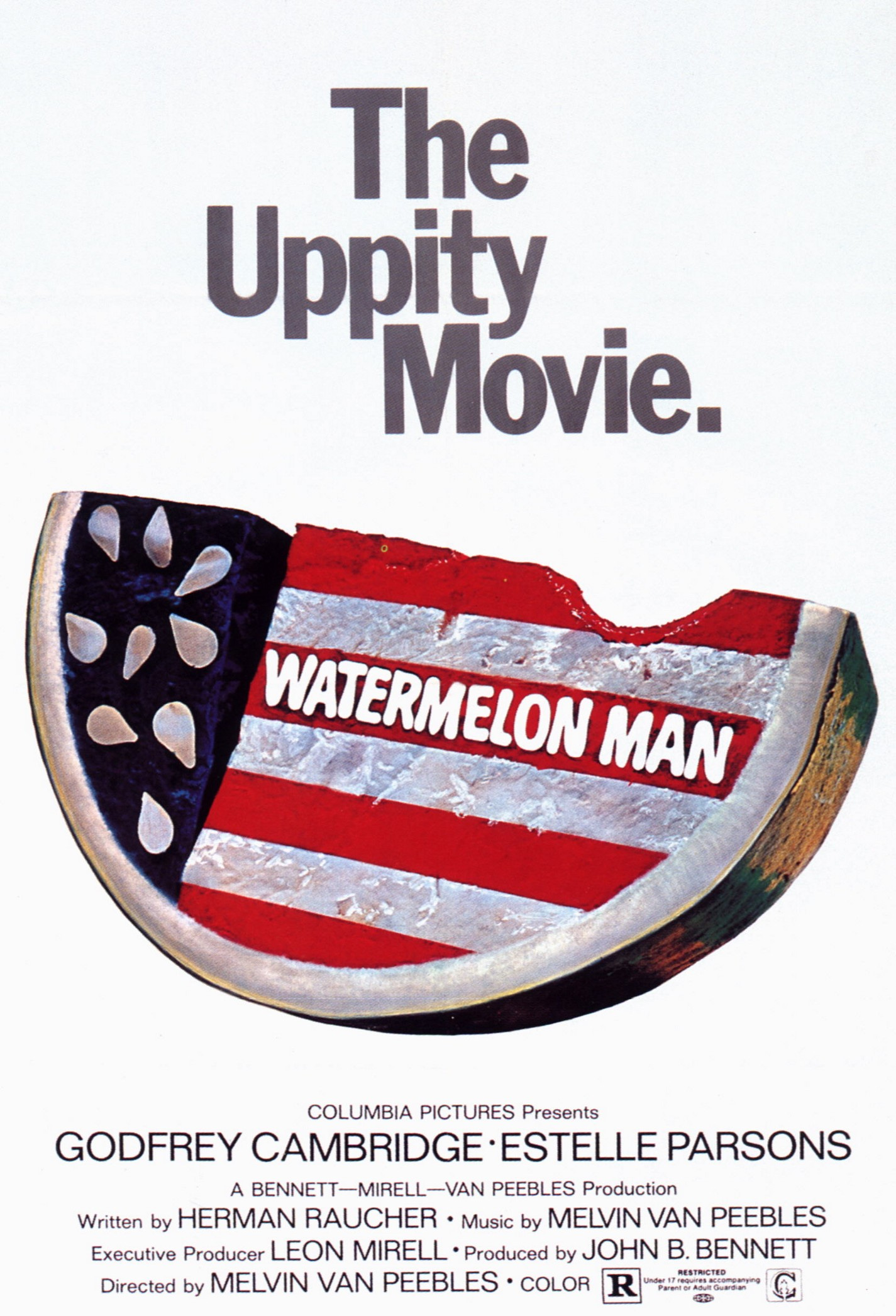

Blaxploitation Education: Watermelon Man

Definitely a problematic movie, but it at least has something to say.

As my Blaxploitation series continues, we get to a weird entry that seems to fit into the gap between the point when studios realized that Black people were a lucrative audience and when they figured out what they actually wanted to see.

Watermelon Man

Written by Herman Raucher

Directed by Melvin Van Peebles

1970

Oof, just saying or typing that title makes me uncomfortable. This is a comedy about a white guy who wakes up one morning as a Black man, and apparently the studio thought that hilarity would ensue. As offensive as the title and probably the thought process behind greenlighting the movie was, all I can say is thank god they brought a Black director on board, because otherwise, this would have been a total nightmare. As it is, it’s still got plenty to object to, but it does what it can to treat the concept with at least a little bit of thought and sensitivity.

The studio originally wanted a white actor to play the main role, which would have required him to perform in blackface. Thankfully, the director they hired, Melvin Van Peebles, nixed this idea. He had only directed one film previously, The Story of a Three-Day Pass, which was an adaptation of his own novel. It was produced in France and got some acclaim at film festivals, so he was given at least some measure of control over this misbegotten mess of a movie. This would be the only movie he made through the studio system though, and he would go on to create films independently, including a future entry in this series, Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song. He was something of an iconoclast, so he definitely did what he could to make Watermelon Man work.

Godfrey Cambridge, one of the stars of Cotton Comes to Harlem, plays the main role here. He starts the movie off in whiteface, playing the character of Jeff Gerber, middle-aged insurance salesman, as an obnoxious, bigoted asshole, one of those guys who thinks he’s much funnier and more enjoyable to be around than he is. It’s kind of like a proto-Dave Chappelle character, playing up the stiff, nerdy characteristics of stereotypical white guys but also adding an over-the-top loudness that is somewhat typical of comedy performances in that era.

We get to see a day in Gerber’s life as he races his bus to work, which is part of his regular morning routine, mostly to annoy the other passengers but also to give him a chance to make comments to the Black bus driver (D’Urville Martin, a future Blaxploitation mainstay) about how not too long ago, he would have had to sit at the back. He stops in at a diner for a health drink and makes condescending remarks to the guy behind the counter, who is played by Mantan Moreland, an actor who performed in blackface most of his career. Moreland genially agrees with everything Gerber says and acts in the expected subservient manner, but we get the sense that he knows the role that he’s playing and is as sick of this guy’s bullshit as everyone else.

At the office, Gerber acts like a jerk to a Black elevator attendant, sexually harasses a Swedish secretary, and argues with his boss about his performance as a salesman, all of this being the kind of behavior he knows he can get away with because he’s white. When he gets home, he complains that his wife (Estelle Parsons, who won an Oscar for her performance in Bonnie and Clyde) is watching news about race riots, because he’s sick of seeing all that “uppity” behavior. Then, he rebuffs her sexual advances, claiming that he just doesn’t want to have any more children, that he’s too tired, and other lame excuses.

This guy is just generally loathsome and annoying, and unfortunately, he doesn’t change too much when he wakes up to find that he’s Black, at least not at first. There’s no explanation for this, although he suspects that maybe he’s been spending too much time under his sun lamp. After discovering the change, he spends a lot of time denying it, stating to his wife and everyone else that he’s not a Negro, and trying to find some way to turn himself white again. It gets kind of tiresome, and it goes on for way too long, accompanied by a grating score that seems to try to emphasize every moment of supposed comedy.

However, things perk up a bit once Gerber decides to try to get back to his normal life. He’s accepted that he’s Black now, so everyone else will have to live with it too! This goes about as well as you would expect. When he tries his bus-racing routine, all the white people in the neighborhood freak out and call the cops on him, sure that he’s stolen something. He only gets saved by the Black bus driver, who convinces the cops that he’s a regular passenger.

At the office, everyone is shocked, but they seem to accept him after they recognize his voice and mannerisms. His boss gets the idea that he can now sell insurance to Black people, who were an untapped market because they had never hired a Black salesman. He tries to meet a client for lunch, but they won’t let him into the fancy yacht club where the meeting was supposed to take place, and this inadvertently sparks another race riot. Then, when he returns home, he finds that his neighbors have begun calling his house incessantly, urging him to move and calling him racial slurs.

And that’s kind of the rest of the movie, as Gerber slowly begins to realize that everyone is now going to treat him as a second class citizen. There are some jokes, but they’re mostly quips that Cambridge provides in his nicely ironic manner as he’s presented with each new indignity. His doctor, after running a bunch of tests to try to find out what happened, gives up and refers him to a Black doctor, since he obviously can’t be a patient at that office anymore. When he actually does start to make connections with Black clients and begins to build relationships, his boss gets mad that he’s not just selling them policies, believing that they’re not intelligent enough to understand anything about insurance anyway.

Things come to a head when Gerber’s neighbors get together and make him an offer on his home because they believe having him in the neighborhood will lower their property values. He takes the opportunity to extort them out of as much money as possible, since they and the bank are apparently willing to pay any price to get rid of him. But his wife, after previously seeming supportive during this predicament, gets upset at him for taking advantage of them. Then she gets the chance to turn the tables on him and turn down his sexual advances, and she eventually decides that even though she’s liberal, she just can’t handle this lifestyle, so she takes the children and leaves him.

This leads to what’s probably the most incisive scene in the film, in which he hooks up with the Swedish secretary, who has suddenly taken an interest in him. After they have sex, she goes on and on about how great he was and how she only wants to have sex with Black men from now on, and he just gets more and more uncomfortable, realizing that this fetishization is just another form of the bigotry that he now has to experience every day. And then when he decides to leave, her anger very quickly devolves into calling him racial slurs and even yelling “Rape!” out her window, illustrating the dangers that white women can pose in these situations. It’s a striking, angry scene, a demonstration of how quickly interactions that Black people have with white people can turn ugly.

I can’t say that this is a good movie, but it’s better than I expected, if only because Van Peebles took the issues it raised somewhat seriously. He refused to allow the film to have an ending in which Gerber was “cured” and became white again, because being Black is not a disease or something to be ashamed of. While he doesn’t completely manage to sell the comedy, he does bring some interesting style into the movie, flashing a series of colored filters over the picture at the moment Gerber discovers his change and at other moments when he’s freaking out about his situation.

There’s also a weird bit where, after being chewed out by his boss, on-screen titles encourage Gerber to act as a credit to his race before there’s a smash-cut to him working in a garbage dump. It’s accompanied by a jazzy song (“Love, That’s America”) that was written and performed by Melvin Van Peebles, with lyrics that emphasize the anger felt by Black people in America. There was barely an outlet for that type of anger at the time, and it’s understandable that it continues to be expressed to this day through rap music, films by Black directors, and other forms of media.

That’s probably the real legacy of this movie, as an early example of Black creators demonstrating both the large-scale oppression their people were experiencing and the small-scale indignities of being treated like they are less intelligent, less worthy of respect, and more dangerous just because they have a different skin tone. It might be the best that could be expected while working within the system of a studio that wanted to cast a white man in blackface and make this a silly romp. But while it definitely isn’t perfect, it’s like a slap to the face that attempts to make people wake up and see what is happening around them. As Black filmmakers got more freedom to make the kinds of movies that Black audiences wanted to see, more of those slaps would be coming soon.