Blaxploitation Education: Top of the Heap

Sometimes auteurist visions are compelling, and sometimes they aren't.

Between this movie and Bone, it’s apparently weirdo week on the Blaxploitation beat…

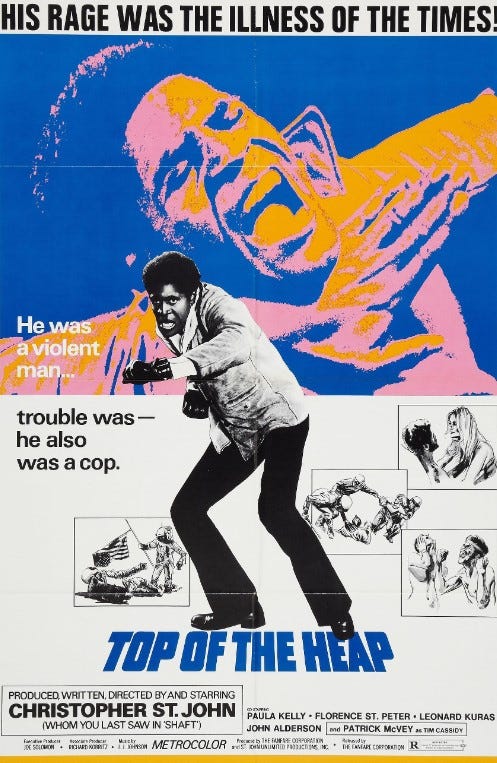

Top of the Heap

Written and directed by Christopher St. John

1972

With this series, I’m trying to be pretty comprehensive, watching as many movies as I can that fit into the Blaxploitation genre. However, that means that in addition to the memorable hits and the crowd-pleasing favorites, I’m occasionally going to delve into the odd fringes of the scene. That’s definitely where Top of the Heap fits, being a strange auteurist piece that must have meant something to its creator but is kind of hard to parse 50 years later.

This movie is the vision of Christopher St. John (Shaft), who wrote, directed, produced, and starred. Unfortunately, as a multi-hyphenate filmmaker, he tends more toward the Ed Wood end of the spectrum rather than being the next Orson Welles. The story follows a Washington, D.C. police officer named George Latimer who seems to be going through a mental breakdown following the death of his mother and the ongoing pressures of the job, his family responsibilities, and just being a Black man in the United States. We spend the whole movie in his head, and it’s a strange place, with him regularly deviating into fantasy and occasionally exploding into violence after he comes back to reality.

While St. John does seem to be trying to explore the difficulties his character faces as he experiences a lack of respect from his fellow officers, the public, and his family, he doesn’t exactly make the guy very likeable. He’s an angry man, brushing off any condolences that people offer about the death of his mother, rejecting suggestions that he should keep trying to apply for a promotion after being rejected repeatedly, and reacting violently against people whether he’s in or out of uniform. He doesn’t seem to have much interest in his family, mostly blowing off his wife when she tries to get him to talk to their 13-year-old daughter after she was caught messing around with a neighbor boy. When he does finally talk to her, he finds out she’s been taking pills, but rather than trying to do anything about the situation, he takes out his anger by beating up a random drug dealer.

We do get some idea of what has been pushing George to this dark place as he deals with racism from nearly every direction. People he arrests call him racial slurs, and some Black drug dealers call him a pig. When he pulls his gun on a guy on a bus who starts threatening the bus driver, a white cop nearly arrests him. When he almost gets in an accident and starts an altercation with the other driver, the guy calls him a Black bastard and complains about “his kind” before backing down once he realizes that George is a cop. It’s understandable that he’s constantly on edge, although he doesn’t seem to be helping things by treating everyone around him so poorly.

On its own, all of this could be kind of compelling, but rather than focusing on what’s happening in George’s life, the movie devotes a great deal of time to his fantasies. He regularly drifts off into visions of what his life could be like if he got some respect, imagining himself as an astronaut who gets respect and adulation. Unfortunately, these flights of fancy are interminable, with scene after scene of George striding down white hallways, floating in space, and consulting with NASA bigwigs (who are played by other people in his life, actually affording him the respect he thinks he deserves). They also stray off into some surreal directions, like a scene in which he sees his mother and randomly starts dancing with her before she turns into a sexy African woman.

But even these fantasies don’t really give him what he’s looking for. A scene in which he and another astronaut are on the moon starts out kind of surreal, with the flag they plant being upside down and the other guy not knowing how to salute when George takes his photo, before it turns out they’re on a soundstage filming these scenes (it seems to be a rehearsal rather than an example of conspiracy theories about the moon landing being faked). In another scene where George imagines returning to his hometown for a triumphant welcome, he finds that the town is empty, with nobody there to celebrate him. Even in his own mind, he can’t find happiness or satisfaction.

With so much of the movie being devoted to George’s inner life, you might think that we would be on his side, understanding the problems he is facing and the reasons he’s so unhappy. But no, he mostly comes off as a jerk, somebody who doesn’t like his life, doesn’t see any positivity in the future, and doesn’t feel like he has any other options. At one point, he tells his wife that he’s done being a cop, and when she understandably gets angry at him because he’s the family’s source of income, he just yells at her that he doesn’t care about money anymore. He also has a side piece (Paula Kelly [Cool Breeze], whose character doesn’t even have a name in the credits, only being referred to as “Black chick”) who seems to mostly laugh at him, get high, and make up songs when he visits her apartment. At one point, he goes to the nightclub where she works and tries to leave with her. When the owner objects, George beats him up and gets into a fight with other employees. After they get out of there, he tells his girlfriend he wants to run away with her, but she asks what they’re going to do for money, since he just made her lose her job. This makes him see her as just another nagging woman like his wife, so he throws her out of the car and leaves her behind. He’s just not a pleasant person to spend time with, and living out his bizarre fantasies along with him certainly doesn’t help us get on his side.

I can kind of see what St. John was going for here, delving into the pressures that Black men face, but as a character study, this movie is a pretty unpleasant one. With so much of the runtime being devoted to strange, nonsensical fantasy sequences, as well as scene after scene of George being a jerk to everyone around him, I got to the point where I was just wanting it to be over. As I said above, I’ll be experiencing some odd corners of the Blaxploitation world as I watch these movies. While there’s often some interest in the nooks and crannies of the genre, I’ll also be happy to get back on the main track and experience the satisfying entertainment that so many of these films had to offer.

Blaxploitation Education index:

UpTight

Cotton Comes to Harlem

Watermelon Man

The Big Doll House

Shaft

Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song

Super Fly

Buck and the Preacher

Blacula

Cool Breeze

Melinda

Slaughter

Hammer

Trouble Man

Hit Man

Black Gunn

Bone

It says "Metrocolor" at the bottom of the poster- since that was MGM's in-house photo lab, I can only assume they either bankrolled it or St. John rented it from them while producing independently.

(Have you considered doing another weird MGM blax film, "Sweet Jesus Preacher Man"?)