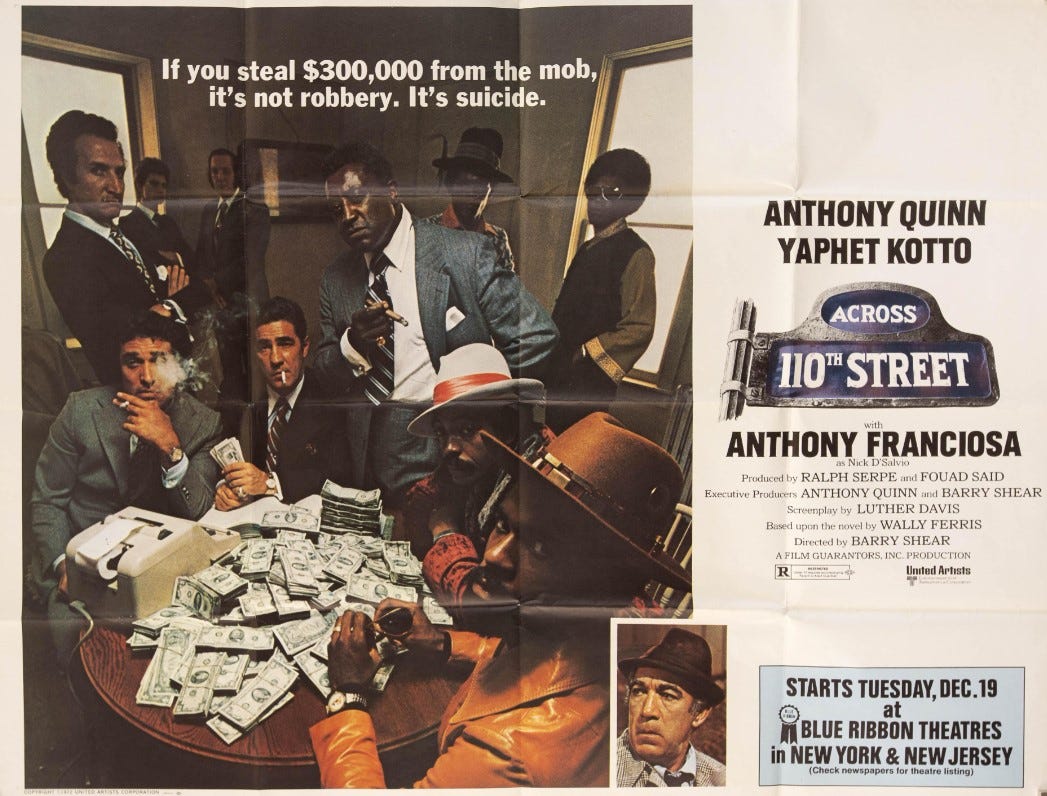

Blaxploitation Education: Across 110th Street

Some crime movies can be pretty nihilistic, which befits the ugly world we live in.

Across 110th Street

Written by Luther Davis

Directed by Barry Shear

1972

The 1970s is known as something of a high water mark for American film, with plenty of movies that featured morally complex stories that provided showcases for actors who were developing compelling, naturalistic styles, as well as directors who were set loose and given free reign to come up with exciting ways of depicting action and drama on screen. The era was also known for movies that were somewhat depressing, featuring unhappy endings in which the protagonists didn’t survive and justice wasn’t served. That negativity didn’t necessarily extend into the burgeoning Blaxploitation movement, which often fought against this trend by featuring Black heroes who, through their culture’s learned ability to survive oppression, were able to achieve victory over racism and provide audiences with something to cheer about. But that wasn’t always the case.

Across 110th Street seems like it’s importing ideas from the white end of 70s film, attempting to replicate the feel of something like The French Connection. It’s got crooked, racist cops, violent gangsters, and characters who were doomed from the moment they tried to strive for something more than they thought they could have expected out of their lives. It’s a real downer, offering little in the way of hope for an American culture that was plagued by racism and inequality and served as a breeding ground for violence and exploitation. It’s horror on a social scale, leaving its characters and audience shaken by the awfulness they’ve witnessed.

The story involves a robbery in Harlem by a few Black guys who happened to be “lucky” enough to figure out that a mafia cash handoff was taking place. When they try to stick up the money men, things go south, and it turns into a massacre, with seven people being killed, including two cops who showed up to the scene in response to the machine gun fire. Since the robbers are pretty small-time, they’re located incredibly easily, and the movie ends up being something of a race between the police and the mafia to see who will track them down first.

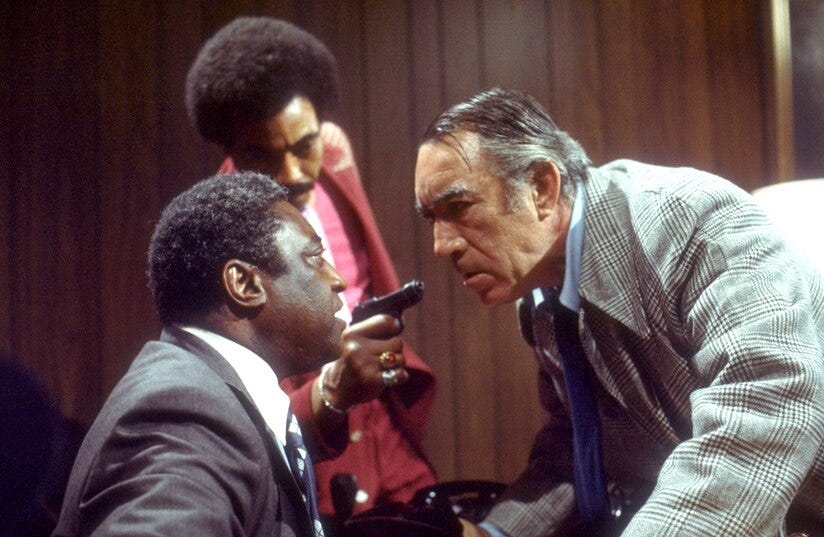

That’s the basic framework for the story, and there’s not much else to it, so the real meat of the movie involves filling in the details. One of the main cops on the job is Captain Mattelli (Anthony Quinn), a racist asshole with an angry, violent streak who sort of thinks he’s doing his job, but that involves brutalizing nearly every Black person he comes across, either trying to beat confessions out of them or threaten to do so if they don’t give him the information he wants. He’s joined by Lieutenant Pope (Yaphet Kotto, Bone), a recent import from Los Angeles who wants to prove himself as someone worthy of respect but has trouble doing so as he navigates a corrupt, racist system.

On the mafia side of things, there’s Nick D’Salvio (Anthony Franciosa), a guy with a real chip on his shoulder who seems to think he has to prove himself as he ventures from his regular stomping grounds in Manhattan to where the title indicates, trying to get the mafia’s Harlem associates to respect him even though he’s only in a position of prominence because he’s the boss’s son-in-law. He’s all too happy to show off his racist attitudes, doing things like shouting the n-word when entering a nightclub so everyone will pay attention to him as he viciously beats the guy he’s chasing down.

As for the three robbers, it’s pretty clear that they’re over their heads from the moment they decide to take on a powerful crime organization. However, they seem to feel like they have no other choice. In a powerful scene, the wife of Jim, one of the robbers (Paul Benjamin, who made a few appearances in Blaxploitation movies, as well as later films like Do the Right Thing and Rosewood) begs him to turn himself in to the police and give the money back, knowing that it’s going to get him killed. But he refuses, saying that since he’s an ex-con, he doesn’t have any options. He’s doomed to barely scrape by for the rest of his life, with the best scenario being working in menial jobs and feeling miserable, and this is his only possible ticket out of that life. Even if the chances of survival are pitifully low, he feels like he has to try, if only to feel like he did what he could to succeed and escape an increasingly desperate situation. It’s a horribly sad scene, one that gives everything bad that we know is going to happen later an undercurrent of tragedy as we see people who have been left behind by society get inexorably pulled into the insatiable maw of violence.

Jim’s compatriots cut figures that are a bit less overtly tragic, but still sad as we see their actions bear fruit and lead to violent death. The group’s driver, Henry (Antonio Fargas, from Shaft and many other Blaxploitation movies), doesn’t bother to hide out or try to get away; instead, he immediately dresses up in a fancy 70s getup featuring a wide-brimmed hat and a multicolored jacket and starts throwing money around at a local brothel. That’s where he gets found by Nick and basically tortured to death.

This prompts a kind of interesting scene in which Mattelli and Pope go to confront Doc Johnson (Richard Ward), the head of organized crime in Harlem, telling him that there will be no more “crucifixions.” Johnson, however, doesn’t really care what Matelli has to say, revealing to Pope that Matelli has been accepting bribes from him for pretty much his entire career in the force. Matelli insists that he only accepts money from gambling rather than anything that comes from drugs or prostitution, but Johnson lets hi know that it’s all the same money from his point of view. He also assumes that he’ll have a similar relationship with Pope, doing what he can to further his career if he’ll just look the other way every now and again. You can see the corrupt system persisting, the powerful forces of exploitation dragging everyone down to the lowest level possible.

It seems that we’re supposed to feel for Matelli, given that he’s played by the biggest star in the movie, and he seems to be troubled by the fact that he’s nearing the end of his career and doesn’t feel like he made much of a difference in all those years. But it’s hard to do so when he’s so unpleasant to everyone around him and especially to the Black community he’s supposed to serve, treating them like every single one of them is a criminal who he can’t wait to beat up whenever he feels like it. Even at the time, he must have seemed like a pathetic old man who was struggling to deal with the fact that the world had changed around him. From the standpoint of several decades later, he’s a representation of everything that’s wrong with white authority figures. Rather than feeling any sort of compassion for his struggles, I was ready for the violence of this world to extend to his corner of it.

So, everything mostly ends up as you would expect, although the finale ends up being a shootout that’s thrilling in its level of violence and deeply sad due to its senseless waste of human life and potential. Really, that’s this movie as a whole. It’s a nihilistic visit to a world where there’s little worth fighting for, but people can’t help but scrabble for purchase on an increasingly slippery slope to hell. It’s a place worth visiting if you want to vicariously experience some of the worst that this world has to offer (as well as nicely funky score and a soulful theme song from Bobby Womack), but I sure as hell wouldn’t want to live there. I think it’s important to remember that random chance is the only reason that I don’t.

Blaxploitation Education index:

UpTight

Cotton Comes to Harlem

Watermelon Man

The Big Doll House

Shaft

Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song

Super Fly

Buck and the Preacher

Blacula

Cool Breeze

Melinda

Slaughter

Hammer

Trouble Man

Hit Man

Black Gunn

Bone

Top of the Heap

This is another film with an amazing soundtrack, the joint work of soul legend Bobby Womack and master jazzman J.J. Johnson. The title song is a movie unto itself ("Across 110th Street...you can find it all in the street...").

Fargas did appear in many blax films in the genre's prime, but I know him best for his wicked turn as the comic pimp "Fly Guy" in Keenan Ivory Wayans' hilarious parody of the genre, "I'm Gonna Get You Sucka", from the late 1980s. (Like "Across 110th", it was distributed by United Artists).

One of my favorite movies from the 70s. Every scene seems to be intentionally painting New York as a trash strewn, dirty hellscape, which matches the hard boiled narrative. Great soundtrack too.