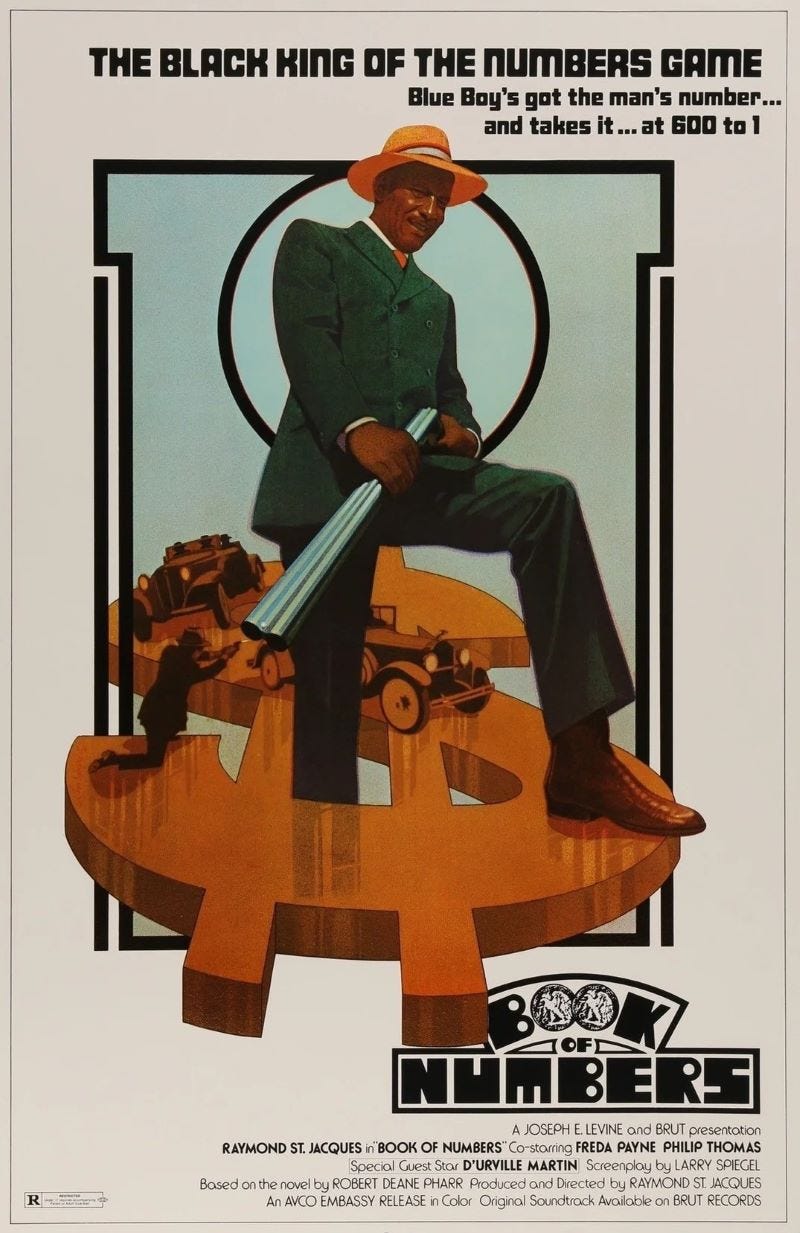

Blaxploitation Education: Book of Numbers

Period pieces could also fit into the Blaxploitation mold.

Book of Numbers

Written by Larry Spiegel

Directed by Raymond St. Jacques

1973

While the Blaxploitation genre often focused on modern-day stories involving crime in urban communities, plenty of other subgenres fell under its umbrella, including period pieces. By 1973, there had already been a few Blaxploitation Westerns (Buck and the Preacher, The Legend of N***** Charley), and Book of Numbers adds another subgenre, sort of functioning as a Blaxploitation version of a 1930s gangster movie, albeit one that’s focused on the racism experienced by criminals operating in the American South at the time. However, it’s not too different from a number of other Blaxploitation crime movies, although the period and location allow the white villains to be even more openly racist than usual.

The movie is based on a novel by Robert Dean Pharr, and it’s directed by one of its stars, Raymond St. Jacques (Cotton Comes to Harlem, Cool Breeze). The other lead is played by Philip Michael Thomas (who is best known as one of the stars of the TV show Miami Vice) in one of his first roles. It’s an independently-produced, low-budget film, but it makes the most of what it has by building out an interesting setting and populating it with memorable characters, then having them struggle for survival as they deal with rivals, racists, and the law. It’s not bad at all for a movie I’d never heard of until stumbling across it as part of this project.

The story takes place sometime in the 1930s, and it follows Blue Boy (St. Jacques) and Davy (Thomas), a couple of guys who have managed to save up a little money working as waiters and want to make something of themselves by starting a numbers operation in El Dorado, Arkansas. Blue Boy is older, and he seems to serve as something of a mentor to Davy. He’s sure that he can pass Davy off as an experienced gangster from New York City, despite Davy’s misgivings, which are usually conveyed via voiceover, as often happens when movies are adapted from novels.

For those who don’t know (which included me before I started watching these movies), the numbers racket is like an informal lottery that is usually operated by organized crime. Regular people can place bets on a number that is randomly drawn on a daily basis, and they can get a large return if their number is selected. As with all forms of gambling, it’s incredibly lucrative for the people operating the scheme, so before long, Blue Boy and Davy are rolling in dough. They set up operations in the back of a local beauty parlor, and they soon have a bunch of guys working for them (including one played by D’Urville Martin, who by 1973 was quickly becoming one of the most prolific Blaxploitation actors, having appeared in movies ranging from Watermelon Man to Black Caesar). Of course, this brings them to the attention of other criminal figures of the whiter persuasion, so before long, they’re going to need to defend their turf.

But before that, the movie spends some time developing this community. Blue Boy is from the area, so when he and Davy step off the bus, they’re welcomed by a number of locals, who are happy to treat them to a home-cooked meal and encourage them in their efforts. We get several scenes in which they attend church, complete with extended gospel songs and an exuberant sermon. There’s a real sense of community here, with Black people working together to build each other up and succeed. It’s the kind of thing that is gratifying to see, even though we know how angry it makes racists.

And sure enough, some other criminals start trying to take down the numbers operation, steal the money that has been made, and run them out of town. There’s a pretty exciting fight scene following a failed robbery, and even though the robbers are Black, it sure seems like there’s somebody white behind it (Blue Boy says, “I smell something burning, and where there’s smoke, there’s a peckerwood.”). That turns out to be a local crime boss (Gilbert Green) who is ready to run these upstarts out of town.

There’s some back-and-forth violence that ensues, but one sequence is especially notable in the way Davy and Blue Boy’s gang gets one over on the other side. When some Black robbers working for the white crime boss rob the beauty shop and steal the slips used to run the numbers game, the team is worried that they’ll have to cease operations. They come up with a scheme to get the stolen materials back in which they dress up in KKK hoods and burn a cross in front of the robbers’ house. After the robbers take off running, the faux Klansmen are free to load the materials into their car. But unfortunately, this attracts the attention of some real Klan members who were driving by, and they decide to join in on the activities. After the scheme is revealed, the Black gangsters beat up the Klansmen and take off, leading to an exciting and kind of wacky car chase. It’s one of those satisfying scenes that were becoming commonplace in Blaxploitation movies in which the racists are a bunch of redneck idiots who get a well-deserved end.

As fun as that sequence is, the rest of the movie is a bit more dramatic, with more and more bad things happening to the characters that allow them to express the difficulties of living in a racist society and being punished just for being successful. When Davy’s girlfriend Kelly (Freda Payne) encourages him to get out of town and leave the violence behind, he refuses, saying, “With all my money, you think I can sit down here and be the owner of a legitimate business? Well I can’t, because to the white man, we will always be n*****s!”

These sentiments of Davy’s play into another crucial scene that follows a raid by the police on the beauty shop in which Blue Boy and several other members of the gang are arrested. Davy wants Blue Boy to hire a lawyer to defend him during his trial, but Blue Boy refuses, saying that bringing in a high-priced lawyer will just let the authorities know that something criminal is going on, which will make them more likely to continue investigating and prosecuting them. So instead, Blue Boy and the other defendants show up to the trial wearing overalls and other clothes that seem to be falling apart, and they act like characters in a minstrel show, being extra-loud as they pray and quote scripture. By making themselves look like uneducated hicks (combined with the fact that the money that would have served as evidence has suspiciously disappeared into the pockets of the arresting officers), they convince the judge to let them off.

While Blue Boy sees this as a victory, Davy is horrified that he would stoop to that level. Seeing Blue Boy “bowing and scraping” before the white man and pretending to be inferior makes Davy sick, and it seems to be a sign that they’ll never be able to get any respect. But Blue Boy believes that they’ll never have white people’s respect no matter how they act, so why not play into their racist attitudes in order to take advantage of them? It’s an interesting debate, and it seems like one that was very relevant at the time, with older generations who had learned to survive under Jim Crow clashing with younger people who were fighting to be treated equally. Unfortunately, that fight is still going on, and the way Black people continue to be treated as inferior (like, say, an accomplished, intelligent Black woman who was rejected by a majority of the American public in favor of an incompetent criminal) is infuriating.

For a low-budget movie, Book of Numbers is put together pretty well, with some innovative camerawork and editing that makes things interesting and exciting. There’s one chase sequence that features shots from a handheld camera racing through tall weeds that is visceral and thrilling. There’s another bit where Blue Boy is stumbling down the street in something of a daze after being rejected by Davy, and his point-of-view shots are presented with a fisheye lens that fades to a blur at the edges of the screen, providing a disorienting feeling. It all works really well, making for a really entertaining ride that’s emotional and moving when it needs to be. This is one of those hidden gems that I’m always on the lookout for during this project, and it’s one that I’ll be recommending people check out if they get the chance.

Blaxploitation Education index:

UpTight

Cotton Comes to Harlem

Watermelon Man

The Big Doll House

Shaft

Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song

Super Fly

Buck and the Preacher

Blacula

Cool Breeze

Melinda

Slaughter

Hammer

Trouble Man

Hit Man

Black Gunn

Bone

Top of the Heap

Across 110th Street

The Legend of N***** Charley

Don’t Play Us Cheap

Shaft’s Big Score!

Non-Blaxploitation: Sounder and Lady Sings the Blues

Trick Baby

The Harder They Come

Black Mama, White Mama

Black Caesar

The Mack

This one is new to me. Thanks for the recommendation!

Fromtheyardtothearthouse.substack.com

Criminals who made it rich operating numbers rackets were often able to expand their economic interests into other related fields, such as sports and entertainment, with additional success. A large number of the independent R&B labels of the 1950s, for example, were either directly or tangentially funded by numbers, and it found its way into some of the songs of that time (e.g. Wynonie Harris' bizarre "Grandma Plays The Numbers").

The game is not as common now, because it has been largely been supplanted by legal lotteries offering large cash payouts, such as the multi-state Powerball lottery.