Non-Blaxploitation Education: Sounder and Lady Sings the Blues

Checking in with the more mainstream movies of the era that got some acclaim.

1972 seems to have been a watershed year for Blaxploitation, the point when the genre really got popular, with a large number of films released. But that year also marked a milestone for “Black” movies in general, with two films coming out that received a great deal of praise and multiple Oscar nominations (they didn't win, of course; Black people rarely won Oscars before the 21st century). So while these movies don't really qualify as Blaxploitation, I thought they were worth a look, examining what may have made them stand out to tastemakers and how they differ from their more disreputable cousins that were playing in the theaters on the other side of the tracks.

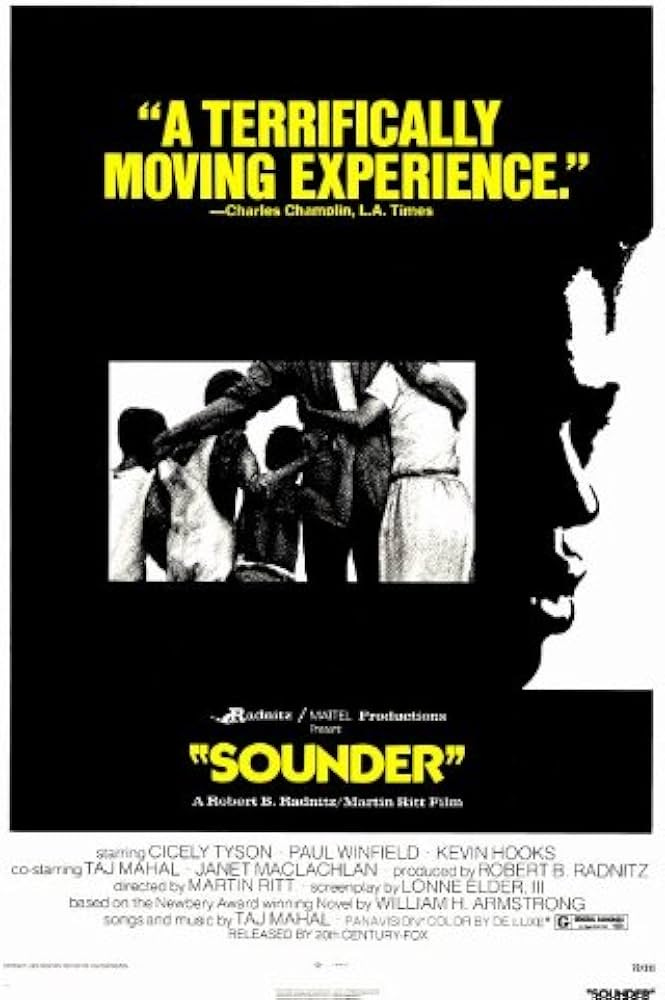

Sounder

Written by Lonne Elder III

Based on the novel by William H. Armstrong

Directed by Martin Ritt

While the Oscars have been known to get things right from time to time and recognize movies and performances that are actually among the best in any given year, it seems that they are more likely to award the movies that are “important “ or fit into certain specific genres that seem to be worthy of praise. This means that “Oscar movies” are often middlebrow stories that seem classy but are ultimately kind of ponderous and boring. I'm sorry to say that at least for me, Sounder fell squarely in that category. It's just literary enough to seem like it's saying something profound, but it's not so confrontational about racism that it would make white audiences uncomfortable.

The movie is based on a children's book, which explains why it doesn't contain anything too upsetting, but that also makes it pretty toothless. It’s about the difficulties Black people faced in the South in the 1930s, but mostly of the economic sort. The racism the characters experience is implicit for the most part, and there’s little in the way of threats or violence from white people. With the writer of the original book being white, and the movie being directed by a white man, it’s easy to see why the ideas presented are somewhat sanitized. (The screenwriter, Lonne Elder III, was Black though; he also wrote Melinda.) The story ends up being uplifting and inspirational rather than a condemnation of how Black people in the United States have continuously been treated as an underclass and subject to constant terrorism by people who could get away with robbing, beating, and killing them whenever they wanted.

The story here follows a family in Louisiana led by Nathan Lee (Paul Winfield, Trouble Man) and Rebecca (Cicely Tyson, who was apparently too classy to appear in any Blaxploitation movies). They’re sharecroppers, and they’re constantly struggling to put enough food on the table. One night after Nathan Lee and his son David Lee (Kevin Hooks) fail to shoot a raccoon for dinner, the father decides to steal some meat from a neighboring farm. As overjoyed as the family is to have something to fill their bellies for a change, it’s not long before the authorities catch up with Nathan Lee, and he gets sentenced to one year of labor at a prison camp. To make matters worse, an officer decides to shoot the family dog, Sounder, and David Lee is heartbroken to lose his beloved pet in addition to his father (don’t worry, the dog recovers; this is a story meant for children after all).

Most of the rest of the movie follows the family’s struggles as they try to get by without Nathan Lee, which requires Rebecca and the kids to do a lot of farm work. The implicit racism they deal with during this time generally has to do with the indifference of the justice system. The local police chief won’t let Rebecca in to see her husband, and they won’t tell the family what prison camp Nathan Lee will be sent to. At one point, David Lee gets some help from a white lady that his family does laundry for, and even though she gets cursed out by the police for sneaking in to their office to look at their files, she manages to get information about Nathan Lee’s whereabouts. So David Lee heads off on a journey to try to see his father, during which he also befriends a Black schoolteacher who encourages him to attend her school and get a good education that will help him in the future.

There’s nothing really wrong with any of this, but it’s all fairly slow-moving, without a whole lot of enticing drama. I didn’t really understand why it was so important for David Lee to spend several days traveling alone to try to get a glimpse of his father, or why it seemed like a big deal to the family for him to attend the other school, which didn’t seem to be all that different from the one he and his siblings went to at home. It just seems like a movie where one thing happens after another, without it adding up to anything especially meaningful.

The performances are generally good. Winfield conveys a sense of stoicism as he accepts his punishment while also clearly wanting to do everything he can to provide a better life for his family. Tyson has a steely determination to make sure her family survives, and she demonstrates a clear love for her husband even while accepting his mistakes.

There’s some decent music as well, with blues musician Taj Mahal providing a score featuring banjos, guitars, and harmonicas and also playing a minor character. I do wish there was more material showing the family and the Black community around them making the most of their circumstances. There’s one moment where Taj Mahal is playing some music in the family’s house, and people start to sing and dance along, but it gets cut short so we can experience more dourness.

Everyone acquits themselves well, but there’s just not much of a framework here for anything other than a basic story about the uplifting nature of the human spirit, or something like that. This seems like the kind of movie about Black people that white people like, featuring strong characters in difficult circumstances working hard to succeed, without any indication of what’s really preventing so many people in their community from doing so. It’s all rather nice and proper, but I found it to be fairly boring, which is why it’s generally more of a footnote in movie history than anything else.

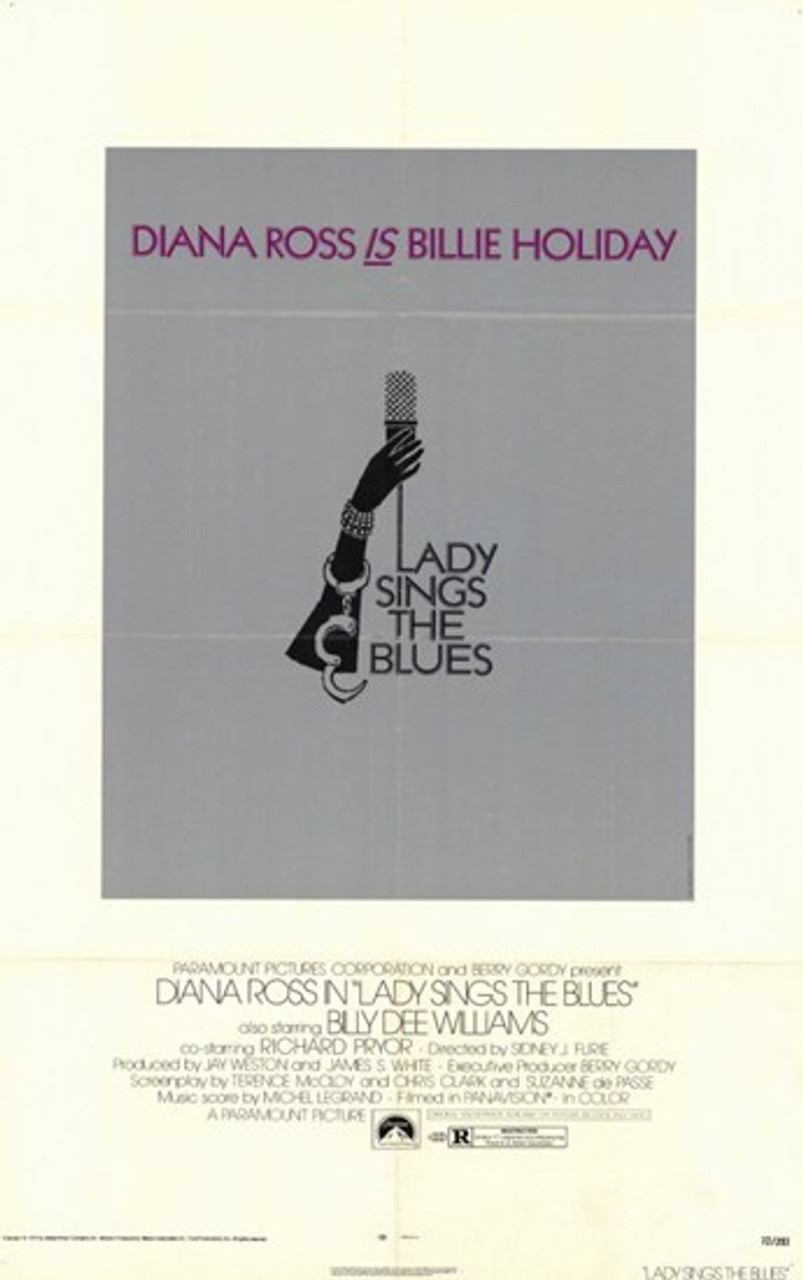

Lady Sings the Blues

Written by Chris Clark and Suzanne De Passe

Directed by Sidney J. Furie

This movie gets a little bit closer to the Blaxploitation spirit, but it’s still solidly within a specific category of Oscar movies: the biopic. That subgenre is a near-constant winner, and when actors (or better yet, singers with limited acting experience) play recognizable figures, that’s often an easy path to a nomination. Here, Diana Ross plays Billie Holiday, not only giving her a chance to do a lot of singing, but also to try really hard to depict trauma related to drug addiction and other issues that occurred during Holiday’s difficult life.

The movie is generally fine, but it follows the bog-standard musician biopic formula, with a path that involves early success, making it big, experiencing difficulties, then having a successful comeback before dying tragically. It works well enough, even though I’ve seen this story many times before. In fact, the movie sometimes seems to just proceed through the expected moments without really justifying why Billie has reached the next stage of her career. When she gets her first singing gig, she’s humiliated by the way the men in the audience try to tip her by leaving dollar bills on the table, expecting her to pick them up between her legs. But she keeps singing, and the crowd eventually stops jeering at her and decides to start cheering for no apparent reason. The movie needs her to become a star at that point, so it’s on to the next thing, and the audience had better just keep up!

Out of curiosity about how much of the movie was true, I read Billie Holiday’s Wikipedia page after watching the movie, where I learned that the plot here only tangentially resembles her real life. The movie makes it seem like she sang in one Harlem nightclub for about a year, went on tour where she started to do heroin, came back to New York and failed to sing on the radio, was arrested and went to jail, went on another tour to rebuild her reputation, came back to play a huge show at Carnegie Hall, then died, with everything taking place over what had to be less than five years. In reality, she had a multi-decade career where she recorded dozens of songs, went on tours throughout the United States and Europe, and played at many major concert halls. She did die at the age of 44 due to cirrhosis of the liver, but she was famous and respected.

While what we see here is pretty far from reality, it’s still a nicely compelling drama. Diana Ross is generally pretty good, although she definitely does some overacting in the scenes involving drug freakouts and the like. She’s bolstered by a strong supporting cast, including Richard Pryor as the piano player who helps Holiday get her first big shot and stands by her throughout her career, as well as Billy Dee Williams (who will be showing up in future entries in this series) as her boyfriend. Williams actually serves as the emotional core of the movie, being a supportive figure who tries his best to help Holiday stay off drugs and seems devastated when she makes bad decisions. (Scatman Crothers also makes a brief appearance, his first of several that I’ll be noting.)

I did like many of the smaller moments and minor choices that Ross made in her performance. She portrays Holiday as kind of goofy and somewhat clumsy at times, really getting the audience on her side and keeping us rooting for her as she falls into bad behavior later on. There are also a few scenes where she and Richard Pryor spend minutes at a time muttering to each other and generally enjoying each other’s presence. It’s the kind of naturalistic acting that showed up in other 70s movies, like the films of Robert Altman, and I wish the movie had stuck with that type of thing instead of going for the big, dramatic moments that mostly rang kind of false.

The movie also only barely touches on the racism that Holiday experienced. We see her be excluded from dining with her white band in a restaurant while on tour. At one point, their bus drives through a KKK rally, and while the band tries to keep Billie hidden, she can’t take it, and she starts screaming at the Klan members, who react violently (in a moment that’s all too resonant in modern times, they smash the bus’s window with an American flag). At one bus stop, she kind of randomly wanders into the aftermath of a lynching, which gives her the inspiration to sing the song “Strange Fruit.” This is all moving stuff, but it almost seems shoehorned in, as if the filmmakers wanted to acknowledge that Holiday dealt with racism throughout her career without making it a focus of the movie.

Overall, it’s a respectable biopic, even if it’s far from groundbreaking. It gives Diana Ross lots of opportunities to sing, and you know she can handle that amazingly. While it does touch on some of the same issues that Blaxploitation movies focused on, it’s much more concerned with showing us the (highly fictionalized) life of a celebrity, and that’s the kind of thing that gets recognition from the Oscars. At least I can enjoy it for what it is.

These two movies managed to get nine total Oscar nominations. Sounder was up for Best Picture, and Paul Winfield and Cicely Tyson were up for Best Actor and Best Actress, respectively. Diana Ross was also nominated for Best Actress, and both movies received writing nominations. They didn’t win anything though. Marlon Brando won Best Actor for The Godfather, and Liza Minelli won Best Actress for Cabaret (the recently-deceased Maggie Smith was also nominated for Travels With My Aunt, I movie I know nothing about). The Godfather won Best Picture. In these cases, I would say the Academy made the right choice.

So did I learn anything from my side trip into “respectable” movies? Well, it seems that I definitely prefer films that focus on real issues that affected Black people in the past, at the time the movies were made, and in the present. The persistence of racism and oppression is a crucial issue that many Blaxploitation movies call out, and I find them to be much more effective than Oscar movies’ glancing acknowledgment that there were problems in the past. And it certainly doesn’t hurt that Blaxploitation movies are much more entertaining, especially when they let audiences live out the fantasy of standing up against oppression, getting revenge on those who harmed Black people, and surviving to win another day. I’ll definitely be glad to get back to seeing more of that.

Blaxploitation Education index:

UpTight

Cotton Comes to Harlem

Watermelon Man

The Big Doll House

Shaft

Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song

Super Fly

Buck and the Preacher

Blacula

Cool Breeze

Melinda

Slaughter

Hammer

Trouble Man

Hit Man

Black Gunn

Bone

Top of the Heap

Across 110th Street

The Legend of N***** Charley

Don’t Play Us Cheap

Shaft’s Big Score!

Both of these movies played a role in expanding the category of Black movies in the mainstream media beyond the shoot-'em-up formula of blaxploitation. Others would follow.

"Lady" was financially underwritten by Motown Records, Ross' label, an effort by company founder Berry Gordy, Jr. to advance the company's media interests at the same time as it attempted to "break" Ross as a mainstream film star. (Her other two major film starring vehicles, "Mahogany" and "The Wiz", also had Motown backing). Screenwriter Chris Clark was a white female soul singer who cut some incendiary pieces that were overshadowed by her romantic relationship with Gordy, while screenwriter Suzanne De Passe would become the supervising executive behind many of Motown's future film and television projects before starting her own eponymous production company.