Blaxploitation Education: The Mack

While pimpin' supposedly ain't easy, this movie makes it seem like it's worthwhile.

The Mack

Written by Robert J. Poole

Directed by Michael Campus

1973

Crime is pretty inextricable from the Blaxploitation genre, and it makes sense that the characters and stories that would connect with audiences operated outside the bounds of the law. During the majority of American history, Black people were shut out from society and refused the opportunities that were available to white people, so engaging in illegal behavior was the only way for many to survive. While some of that had begun to change following the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s, racism at all levels of society most certainly had not gone away, so Black audiences must have been ecstatic to see characters who were not constrained by the rules that had oppressed so many of them for so long. That may have meant that they were celebrating gangsters, thieves, and other criminals, but when these characters are standing up against The Man, it’s hard not to cheer for them.

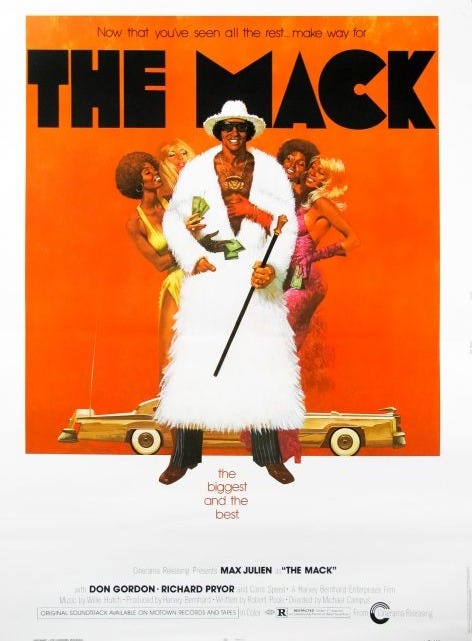

However, the celebration of some types of criminality may be a bit harder to get behind. By 1973, there had already been a few dubiously positive depictions of criminals of the type who are harmful for society overall, such as the drug dealer hero of Super Fly, and The Mack joins that category with its look at the world of pimps. In fact, it’s probably ground zero for the celebration of these flamboyantly-dressed characters whose primary purpose is to place women in what is essentially sex slavery. Fun!

In recent years, this particular category of crime has been looked upon less favorably due to people belatedly coming to understand the difficult idea that women are people who should be afforded the same level of respect and dignity as everyone else. There’s still plenty of misogyny in 21st-century society, but it certainly seemed to be more extensive back in the 70s, leading to at least one movie-length celebration of men who seemed cool because of their mistreatment of women.

I do wonder if my antipathy toward this sort of thing comes from a certain level of internalized racism, as if I believe Black people should be held to higher standards. Is what we see here that different from the ways the gangsters on The Sopranos treated the women around them? Do I give a pass to the white people in crime movies, excusing their behavior as depiction of illegal behavior rather than endorsement? That’s something that I continue to wrestle with. And to be fair, The Mack doesn’t seem to be 100% on board with its main character’s activities. There’s at least a little bit of a gray area, although the bad things that happen because of his actions mostly affect him and the people close to him rather than society at large.

So, to the actual story here: the movie begins in the middle of a shootout after some sort of deal had gone wrong. Our main character, Goldie (Max Julien), ends up crashing a car as he tries to escape, and when a couple of white cops (Don Gordon, who was in Slaughter but surprisingly didn’t show up in any other Blaxploitation movies, and William Watson) find him, they debate whether they should kill him, but decide that would lead to too much paperwork, so they arrest him instead. He gets sentenced to five years in prison, and when he gets out, he’s ready to start down a new path in which he will look out for number one and make enough money that he’ll never end up in that sort of situation again.

Goldie gets some mentorship in the pimp game from a guy who is apparently an elder statesman (Paul Harris, who was in Across 110th Street and will show up in a few more Blaxploitation films). He also gets together with his childhood friend Lulu (Carol Speed, who will be in at least a couple more movies in this series), who all but begs him to be her pimp, since she’s been working as a prostitute and needs someone who can keep her safe.

Goldie also attends a community meeting led by his brother Olinga (Roger E. Mosley, who was in Hit Man but only a few other Blaxploitation movies). He’s not exactly advocating for revolution like some militant Black power groups; instead, he says that Black people need to build each other up and create a culture “within and without” white America. He believes in cleaning up the streets and getting rid of the people who are pushing drugs and prostitution, which is going to put him at odds with Goldie. This could add an interesting aspect of conflict to the movie, but it ends up mostly being a minor subplot.

While some crime movies can make their characters’ rise to power compelling, this is one that mostly skips over that part of the story (similar to Black Caesar). There’s a symbolic scene in which somebody hands Goldie a stack of cash, and he throws it up in the air to rain down around him while he’s sitting in a blank, featureless space. This is also accompanied by shots of him getting some fancy clothes and a tricked-out pimpmobile, so it seems like it could be a fantasy of what he hopes to achieve. But no, the next scene sees him roll up to a neighborhood in his fancy car and be surrounded by a bunch of young boys, who he hands out cash to while exhorting them to stay in school. So apparently he has become a kingpin in the pimp world off-screen.

We do get some hints of Goldie’s criminal activities, with a few scenes in which he and his cohorts (including his buddy Slim, played by Richard Pryor) practice to rob stores by smashing and grabbing jewelry from display cases and stashing clothes under their coats or dresses. While this indicates that he’s not solely focused on prostitution, the sex trade is his main enterprise. He seems to revel in exerting control over the women in his employ. In one scene, he romances a white woman who he has recruited, telling her that by working together, he’s going to make all of their dreams come true, but she has to do everything he tells her to without question. He also gathers his stable of women in a planetarium and has them watch scenes of stars and galaxies while telling them that he’s the ultimate authority in their lives, the center of their universe, and if they keep making money for him, he’s going to take care of them and give them everything they want.

It seems like all of this is meant to be inspiring, but he certainly seems like a manipulator, gaslighter, and abuser. At one point, he’s riding with another pimp and complaining about how he’s having trouble keeping his women (who he refers to as “bitches,” of course) in line. When Lulu comes up to the vehicle in tears, telling him that she’s been abused by a client, he just yells at her that he doesn’t care and she needs to bring him his money. As the film proceeds, it becomes clear that money is his driving motivation, and he’s not going to give up the life that has put him in this position. When Olinga tries to talk to him about improving their community by cleaning up the streets, he says that he doesn’t care about what anyone thinks about what he does; they grew up without money, and now that he’s finally in a financially comfortable position, he’s not going to let anything threaten it.

That attitude drives the main conflict in the movie, which occurs when the city’s drug kingpin, Fatman (George Murdock, who we’ll see in one or two other movies down the line), tries to get Goldie to come back to work for him (which was apparently what he was doing when he got into the shootout at the beginning of the movie). Goldie repeatedly refuses, since he prefers to be in control of his own destiny, and this leads to escalating levels of violence. There are also some conflicts with other pimps and the aforementioned corrupt cops, and when the violence starts to affect Goldie’s loved ones (especially his mom, played by Juanita Moore, who had a memorable role in the landmark film Imitation of Life), it becomes too much to bear, leading to an explosion of revenge that will change his life forever.

This is all fairly interesting as a depiction of a certain corner of the criminal underworld, although I don’t know how well Julien himself holds down the center of the movie. He seems too soft to believably be a guy who would be able to build a criminal enterprise by keeping other people in line. While he does have a certain level of cool swagger, I often found myself rolling my eyes at his proclamations about the importance of money and the reasons why other people should get on board with his vision. His force of will occasionally becomes compelling enough to believe, as in a scene where he tells off Fatman, telling him that he’s a disease worse than cancer who won’t be satisfied until every 10-month-old kid has a needle stuck in his arm. And when he does turn violent, his rage is pretty gripping, with one scene being pretty notable for the way he makes a guy stab himself several times before tying him up, taping a stick of dynamite into his mouth, and blowing him to hell.

There’s a certain allure to the world depicted here, which may be why I’m so conflicted about whether it’s a positive depiction of reprehensible characters. A couple of the movie’s big setpieces involve gatherings of pimps during a “player’s picnic” and “player’s ball,” and we get to see some pretty memorable fashions. The number of giant, fur-lined hats on display in these scenes is higher than I would have thought possible. The movie has some nice music too, with a score by Willie Hutch that features some of the funky 70s rhythms that were becoming a customary part of these movies, as well as songs like “Brother’s Gonna Work it Out.”

This movie seems to be a pretty important part of the Blaxploitation canon, and there’s much to enjoy, but I just can’t fully get on board. It crosses far enough over the line between depicting criminal behavior and glorifying activity that harms people and communities that I found it to be distasteful. Maybe if the main character was slightly more compelling or if it truly examined how the greed of criminals can cause more harm than good, I would be more satisfied. As it is, this is something to experience for those who want a full picture of the Blaxploitation genre rather than a film that can be recommended as a good movie to watch.

Blaxploitation Education index:

UpTight

Cotton Comes to Harlem

Watermelon Man

The Big Doll House

Shaft

Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song

Super Fly

Buck and the Preacher

Blacula

Cool Breeze

Melinda

Slaughter

Hammer

Trouble Man

Hit Man

Black Gunn

Bone

Top of the Heap

Across 110th Street

The Legend of N***** Charley

Don’t Play Us Cheap

Shaft’s Big Score!

Non-Blaxploitation: Sounder and Lady Sings the Blues

Trick Baby

The Harder They Come

Black Mama, White Mama

Black Caesar

Willie Hutch is immensely underrated, and this film has some of his best work. "Brother's Gonna Work It Out" and "Slick" are multi-dimensional accompaniment to the events on screen, and "I Choose You" is one of the best R&B ballads I've ever heard.