Blaxploitation Education: The Legend of N***** Charley

Unfortunately, this isn't the last movie in this series that will have a slur in the title.

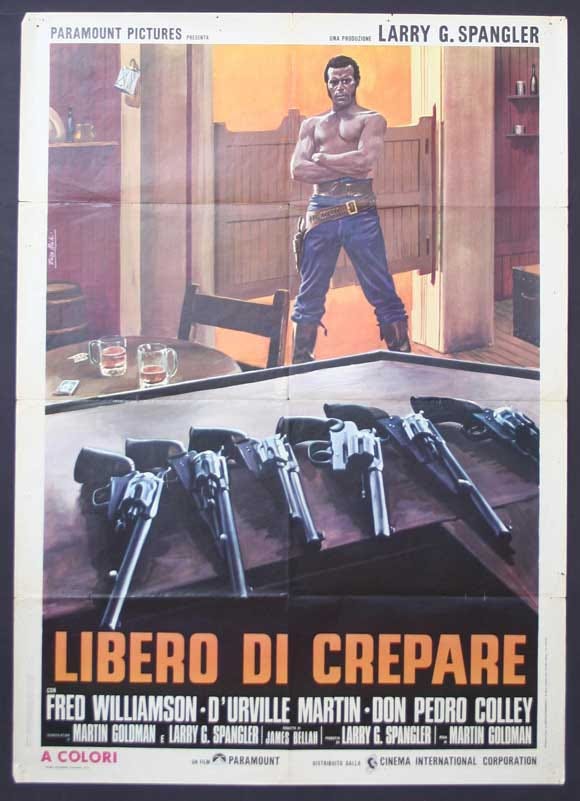

The Legend of N***** Charley

Written by Martin Goldman and Larry G. Spangler

Directed by Martin Goldman

1972

I don’t think the Western was an especially well-trod subgenre of the greater genre of Blaxploitation, but it featured at least a few entries. The Western genre itself may have been somewhat limiting without the ability to directly highlight the concerns of Black audiences in the 1970s, although it does offer the chance to look at the history of racism in the United States, and when done right, like in Buck and the Preacher, it can look at the deep moral rot at the country’s core. But in other entries, the cliches of the genre may have been impossible to overcome.

That seems to be the case with the provocatively-titled The Legend of N***** Charley, which has a pretty good role for Fred Williamson (Hammer), some strikingly ugly examples of racism, and not a whole lot else going for it (except maybe being partially responsible for inspiring Django Unchained?). It occasionally seems like it’s going to have something to say, but it never really does, and its plot mostly just moves along, alternating between misery porn, bursts of righteous anger, and action in which the heroes come out on top because that’s what supposed to happen to movie protagonists.

The story opens with some scenes of African people being rounded up and sold into slavery before fading to a Southern plantation where an old, sick white man is being tended to by a Black servant. He’s apparently one of those mythical “good” slave owners, because when he offers the woman her freedom because she has served him well for 21 years, she refuses, saying she would rather keep working for his family. But she does convince him to free her son Charley. He’s reluctant to do so, since Charley is valuable due to his blacksmithing skills, but she eventually convinces him.

However, while it seems life on the plantation was idyllic for everyone, slaves included, the second-in-command, a racist asshole named Houston (John P. Ryan), is planning to profit from his boss’s impending death by selling off all the slaves. Even after Charley has been freed, Houston treats him like an inferior, even going so far as to barge in on him and his girlfriend while they’re having sex and make threatening overtures. When Charley responds with violence, Houston’s men beat him, tie him up, and lock him in a shed, then they proceed with the slave auction.

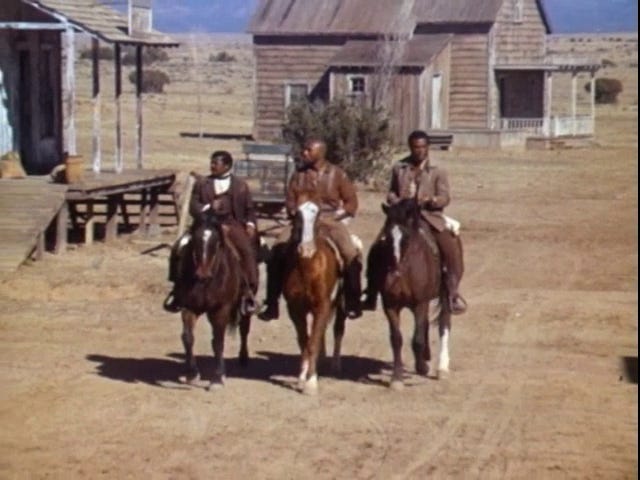

Fortunately, Charley had already been planning an escape with a couple other slaves, Toby (D'Urville Martin, Watermelon Man and several upcoming movies in this series) and Joshua (Don Pedro Colley, also slated to appear in more Blaxploitation movies), and they manage to free him and get ready to ride away on some horses they stole. When Houston, drunk after partying at a post-auction cockfight, decides to appease his sense of inferiority by attacking a helpless victim, Charley ends up beating him to death. So now he and the others are on the run, and they head West.

Perhaps we’re meant to understand that because they killed a white man, Charley and the others are fugitives who have no other option but to try to escape to freedom. But they don’t breathe a word about the people they’re leaving behind, including Charley’s mother and the woman who he promised he would take with him after he was freed. Instead, they just head off into the wilderness, complaining that they’re being tracked by Houston’s pal Fowler (Keith Prentice), a notorious hunter of escaped slaves.

Soon, they end up in a nameless Old West town where everyone stares at them as if they had never seen a Black person before. This is another one of those weird moments in which the movie seems to accede to genre tropes, as if Black people just didn’t exist in the American West. Except the townspeople still call Charley and his friends racial slurs and halfheartedly try to enforce Jim Crow laws. At the local saloon, the bartender refuses to serve them, and patrons try to say that they don’t deserve to be there, which leads Charley to beat a guy up and throw everyone out. But while you would think this would lead them to come right back in and attempt a lynching, they apparently decide to just let Charley and his buddies have the bar to themselves.

At one point, the local sheriff comes in to try to warn them that they’re wanted criminals, and Fowler is coming to kill them. But Charley lets him know they’re done with running, so they’re just going to stay put and stand their ground. The sheriff tries to defuse the situation and get Fowler to leave them alone, but he and his men refuse and start a shootout. Somehow, even though they’re vastly outnumbered, Charley’s group manages to kill all of the assailants, which apparently means they’re free to go on their way.

On their way out of town, a local farmer stops Charley and asks him for his help. He and his wife, who is half-Cherokee, are being harassed by a local criminal who styles himself as a man of god, and they have to deal with constant violence and theft by the Reverend’s men. Charley initially refuses, saying he has his own problems to deal with, but a day or two later, he gets thinking about the man’s wife and considering that she’s also “colored,” so he decides to go back to help them. It seems less like he’s doing so out of altruism and more out of horniness, but the rest of his group decides to tag along too.

So of course, this leads to a climactic shootout with the Reverend and his men, and having won the day, Charley and the friends who survive get to ride off into the sunset. It doesn’t seem like any lessons have been learned though; they’re just ready for their next adventures (which we’ll get to witness in a couple of sequels).

I’m being kind of hard on this movie, but that’s because I found its plot to be pretty disappointing. Like too many cheap Westerns, it features lots of shots of characters riding horses through the wilderness, along with plenty of slow-moving scenes in which nothing interesting happens. After a beginning that featured some horrific racism and indications that it was going to deal with the impossible plight of a Black man who dared to stand up for himself, the movie just kind of meanders into a generic Western plot without putting any thought into what life might actually be like in this setting for a guy who had decided that he was done with being treated like an inferior. As much fun as it is to see Charley and others beat up and kill some racists, victory seems to come too easily.

Fred Williamson does cut a pretty heroic figure, even if he sports some anachronistic 70s sideburns, and he gets a few good lines. When a stable boy objects to him boarding his horse because he’s Black, he shoves some bills into the guy’s hand and says “My money’s white.” (How he got said money as a former slave on the run is unexplained.) Other characters are pretty good too, with D'Urville Martin filling the role of comic relief and countering Charley’s seeming death wish by asserting his desire to live. There’s also a goofy character named Shadow (Thomas Anderson) who wanders into Charley’s orbit because he wanted to see some Black gunfighters. He’s an older fellow who claims that he’s the son of a Sioux woman and a white man who has been wandering through the West, but it’s later revealed that he’s another former slave, and he’s happy to be able to identify with others who have gone through similar experiences.

While there’s some enjoyment here, memorable moments are few and far between. It probably didn’t help that the version of the movie I was able to find online was apparently a copy of an old VHS tape, but it seemed to be pretty indifferently shot anyway, so I don’t think I was missing much. There’s a nice, soulful song (“In the Eyes of God”) over the opening credits sung by Lloyd Price (as well as a theme song over the closing credits that’s less enjoyable, mostly because it features a chorus that repeats the main character’s nickname over and over). I also found it notable that the villainous Reverend (Joe Santos), who chews scenery like crazy in the couple scenes where he appears, misquotes the Bible to serve his own ends (“The Lord says, ‘Blessed are the strong!’”), much like so many continue to do today. But you kind of have to search for the good stuff here, and unless you’re in the midst of a completist project like this, it’s probably not worth the effort.

Blaxploitation Education index:

UpTight

Cotton Comes to Harlem

Watermelon Man

The Big Doll House

Shaft

Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song

Super Fly

Buck and the Preacher

Blacula

Cool Breeze

Melinda

Slaughter

Hammer

Trouble Man

Hit Man

Black Gunn

Bone

Top of the Heap

Across 110th Street

"..as if Black people just didn’t exist in the American West." Tell that to Bass Reeves.