Blaxploitation Education: Black Caesar

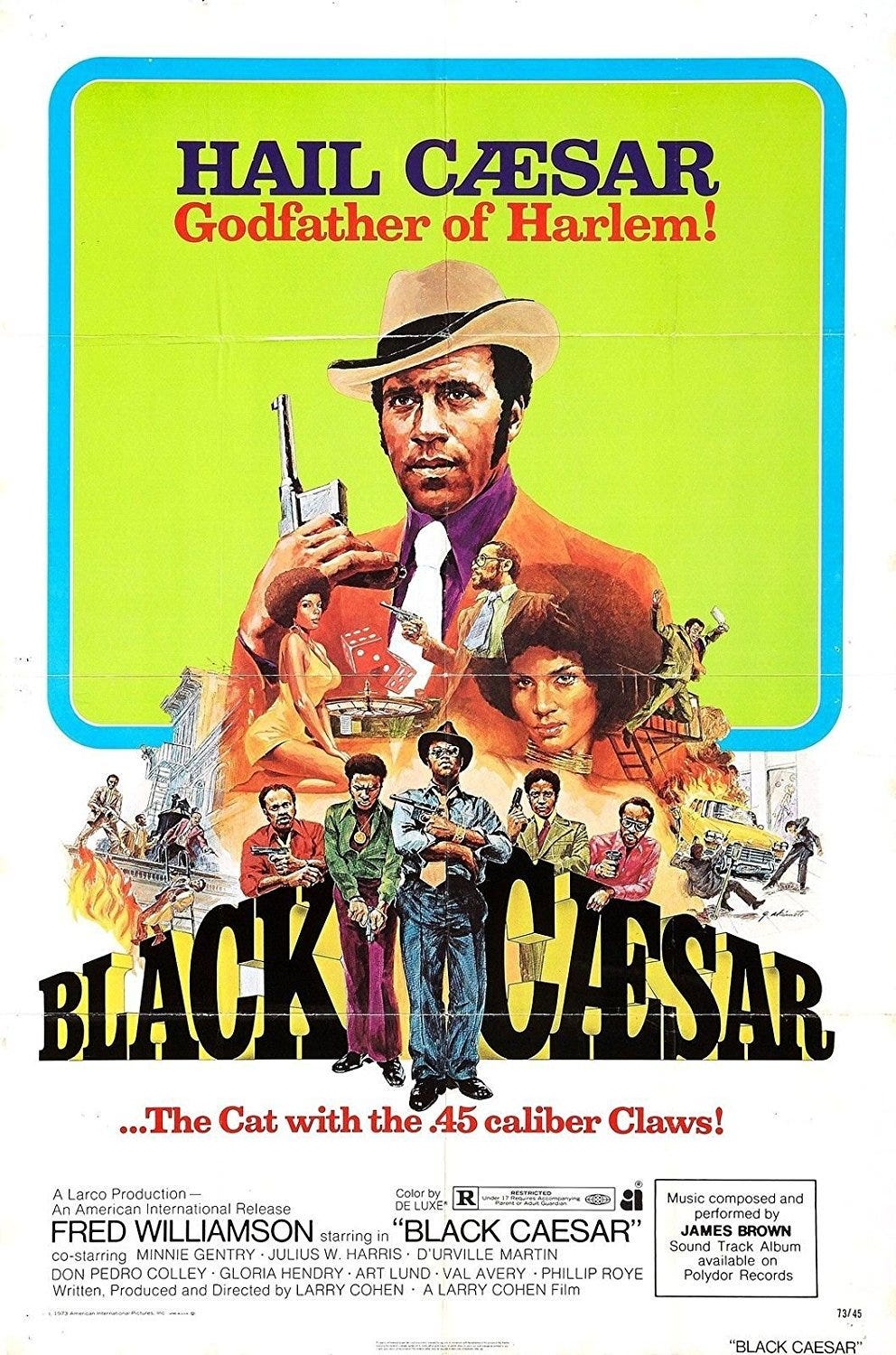

Fred Williamson stars in an attempt at a Blaxploitation version of The Godfather, but Larry Cohen is no Francis Ford Coppola.

Black Caesar

Written and directed by Larry Cohen

1973

While many Blaxploitation movies fit into the general subgenre of “crime,” they were usually focused on street-level activity. Their plots may have involved Black mob bosses, but they were usually subordinate to more powerful mafioso types. But there’s nothing that said they had to remain relatively small-time. If you’re going to make a Black gangster movie, why not go big, treating it like a large-scale mafia story that has been a staple of Hollywood for decades?

That seems to be the idea behind Black Caesar, which is a remake of the 1931 gangster movie Little Caesar, a vehicle for Edward G. Robinson. The story gets updated to take place between the 1950s and the 1970s, and Fred Williamson stars as Tommy Gibbs, a guy who rises from a shoeshine boy who runs errands for gangsters to the highest echelons of the criminal underworld before experiencing a dramatic fall. It’s a classic gangster story told through a Blaxploitation lens, although it departs far enough from the norm that it doesn’t necessarily work as well as the best entries in the genre.

We first see Tommy as a teenager in 1953 who seems to be trying to enter the world of organized crime, first by helping with the assassination of a gangster while shining shoes, then by delivering some payoff money to a cop. But when he shows up to give an envelope to Officer McKinney (Art Lund, who fits the role of the racist Blaxploitation villain really well, although it looks like the only other movie in the genre he appeared in was Bucktown in 1975), the cop complains that people of his race aren’t allowed in the building, then claims that the payment is $50 short, expecting Tommy to make up the difference. When Tommy refuses, McKinney beats him mercilessly. The next time we see Tommy, he’s in the hospital with his leg in a cast, and although it’s unclear, it seems like he’s been arrested and will be spending some time in the custody of law enforcement.

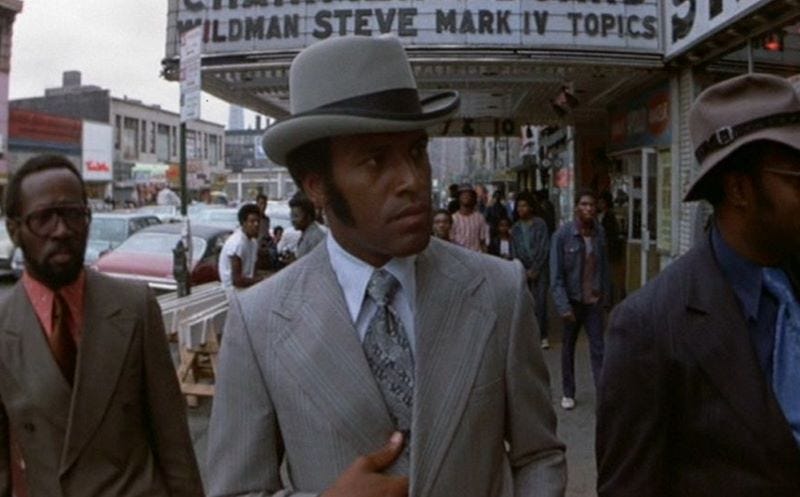

The story picks up in 1965, after Tommy has been released and is ready to make a name for himself in the criminal underworld. He shows up back in New York and immediately goes to a Black barber shop where an Italian guy is getting a shave, making sure to inform the guy that he has a hit out on him before shooting him. Then he goes to a local mob boss named Cardoza (Val Avery), to inform him about the hit and collect his payment. He wants to get hired on as a regular enforcer, but Cardoza says that other members of the mafia wouldn’t be too happy about his employment of a Black man. However, Tommy finally convinces Cardoza to let him have a block of territory in Harlem.

This leads to a montage of Tommy building a criminal empire. We don’t really get much detail about how he does so, but soon enough, he’s one of the city’s most powerful gangsters. He works mostly with a couple of childhood buddies: Joe (Philip Roye) and Rufus (D’Urville Martin, who we’ve seen in Hammer, The Legend of N***** Charley, and Watermelon Man and who will show up in plenty more of these movies), with Joe having the bookkeeping skills to manage operations and Rufus working as a preacher who not only gives their business an air of legitimacy but also lets them launder money through his ministry while avoiding taxes. Some lip service is paid to putting some money back into the community by supporting Black businesses and making sure people have good places to live, but we don’t really see any evidence of this. Instead, Tommy seems happy to earn money through crime and either buy out or rub out anyone who opposes him.

One of the main plotlines involves Tommy finding a way to steal some ledgers from a mafia boss that contain information about illegal activities and payoffs. As long as he possesses this information, he seems to be free to engage in illegal activities without fear of recrimination from other gangsters. You would think that they would try to get some payback after he kills Cardoza and takes over his operations and then guns down an entire pool party full of mafia types, but any comeuppance he receives is a long time coming.

Instead, Tommy focuses on working with two white guys: a local lawyer and politician named Alfred Coleman (William Wellman, Jr.) and the aforementioned McKinney, who has risen in the ranks of the police department and is now angling to become commissioner. After making some criminal deals, Tommy gives Coleman a bunch of money to purchase his high-rise apartment and everything in it, including the furniture, decorations, and even the clothing (after taking a fur coat off Coleman’s wife’s back, he throws a bunch of her fancy clothes off the balcony in order to redistribute the wealth). When Coleman wonders why he wants all of their stuff, Tommy says it’s because he grew up wearing Coleman’s cast-offs and eating his leftovers. We learn what he means in the next scene, when Coleman’s Black maid shows up to work the next morning and is surprised to find her son Tommy there. Yes, all of this has been because he wanted to shame the rich people whose shadow he grew up in and give his mom (Minnie Gentry) the gift of fancy living. But she won’t accept the gift, because she wouldn’t know how to live in this setting. In fact, she’s pretty sure Black people aren’t even allowed in this building.

That’s one of the main conflicts in this movie, with Tommy constantly forcing himself into situations where most Black people wouldn’t be allowed and managing to succeed through sheer force of will. It’s a little bit of a fantasy, since, as I mentioned previously, the details of his operations are kind of murky. We’re just supposed to accept that he has succeeded in all of his efforts and become an untouchable kingpin. But when McKinney does finally decide to start fighting back, it seems a bit too easy to take out all of Tommy’s lieutenants and eventually threaten his life.

But before we get to the movie’s violent climax, it’s worth delving into Tommy as a character. He’s charismatic and usually exciting to watch, but he also reveals himself to be a pretty bad guy. This befits the source material, which was made in a time when gangster movies had to make sure they weren’t glorifying crime, so their characters were portrayed as murderous thugs who got what they deserved in the end. Unlike most other Blaxploitation heroes, who may have been flawed but were still usually pretty heroic, Tommy engages in plenty of sadistic murders, betrayals of people close to him, and even an upsetting scene where he rapes his girlfriend Helen (Gloria Hendry, who was in Across 110th Street and will be in more Blaxploitation movies to come) when she declines to have sex with him. Later, he finds out that Helen is hooking up with his friend Joe, and he beats the two of them pretty mercilessly and kicks them out of his life.

So, he’s a complicated character, and he’s meant to be multifaceted, containing both positive and negative aspects. At least, the film certainly wants him to be, and it tries to deepen him here and there, such as when his father (Julius Harris, who was in Shaft’s Big Score!, Super Fly, and Trouble Man) shows up to reconnect with him. Tommy comes close to killing him because he had abandoned him and his mom when Tommy was a child, but he relents at the last minute when he learns that the reason his father couldn’t share his military income with them was because he and Tommy’s mom were never legally married. Even with these attempts, a lot of Tommy’s character seems superficial. Depending on the scene, he’s either an ambitious and charismatic criminal, a crusader against racism, or a petty and vengeful jerk. While Fred Williamson does his best to give the character depth, he seems a little out of his element at times, as if the character is playacting at being a tough guy. He’s not quite charismatic enough to get us on his side even as he commits more and more acts of reprehensible violence.

When the movie’s big final confrontation comes, we’re kind of caught between cheering for Tommy to get revenge for past wrongs and happy to see him get his comeuppance. After surviving some attempts on his life but being seriously wounded, he finally makes his way to McKinney, who has engineered his downfall by killing almost everyone around him. When McKinney manages to get the drop on him, he holds Tommy at gunpoint and forces him to shine his shoes just like he had done so many years ago. But Tommy manages to overpower him and beat him senseless with the shoe shine box. Before killing him, Tommy rubs shoe polish on his face to make him feel like the Black people he has spent his life mistreating, then calls him “boy” and tells him to sing “Mammy” as he beats him to death. It’s striking stuff, upsetting in its violence but providing some relief as a racist character receives his well-deserved end.

Moments like that seem to have a clarity that isn’t always there in the rest of the movie. It’s meant to be a complex gangster epic, but it’s often unfocused, not giving us enough detail about Tommy’s rise to power and failing to make this seem like a believable criminal underworld, while also failing to give us enough characterization to make us understand Tommy as something other than a violent, self-centered, power-hungry asshole who is more likely to cause harm to those around him than do anything positive.

Writer/director Larry Cohen (who also made Bone and later went on to focus mostly on schlocky horror movies like It’s Alive) does try to bring some style to this movie, even when working with what had to be a low budget (like a number of other Blaxploitation movies, this was produced by Roger Corman’s American International Pictures). In the scene where Tommy is being targeted for assassination, he manages to turn the tables on one of his pursuers and strangle him with a necktie. During the moments where the guy is choking to death, the camera pans to a nearby digital clock, watching the last seconds of his life ticking away. It also cuts to shots of a cigarette billboard that’s blowing rings of smoke, an ironic juxtaposition with the guy who is dying because he can’t breathe. The scene where Tommy beats McKinney to death contains some striking editing as well, intercutting brief flashes of the scene where McKinney had beaten young Tommy in the past and making him relive the experience from the other side of the equation.

Some of Cohen’s other stylistic ideas don’t work so well. When a wounded Tommy goes to Rufus for help, the only response Rufus has is to pray loudly and exuberantly for the lord to heal him. He almost devolves into a fugue state, where he’s just ranting and raving on his knees, ignoring anything Tommy says to him until Tommy just gives up and leaves. This might have been meant to show that Tommy no longer had any solace after driving away everyone who cared about him, but it just comes off as odd.

The final scene sees Tommy wander back to the derelict building where he grew up, where he’s confronted by a bunch of teenage boys. As he talks to them, possibly begging for them to leave him alone or trying to convince them that they shouldn’t mess with him because he’s a powerful criminal figure, all audio except the score drops out, as if his exhortations are falling on deaf ears. The kids end up beating him and leaving him for dead, with the movie ending with his fall from grace completed as he apparently dies (but not really, since a sequel, Hell Up in Harlem, would be released later in 1973).

This movie ends up being kind of unsatisfying, although its ambition is definitely praiseworthy. Cohen was trying for a large-scale gangster epic, but he couldn’t quite get there. However, there’s still a lot to like, including some exciting moments of gang violence and a thrilling depiction of an ambitious Black criminal succeeding even when the odds were stacked against him. It also has a pretty great score by James Brown, featuring a repetition of the song “The Boss,” as well as a cool theme song, “Down and Out in New York City.” I can’t get fully on board with this one, but even if it’s not in the top tier of Blaxploitation movies, it seems fairly essential if you’re trying to get a complete picture of the scene.

Blaxploitation Education index:

UpTight

Cotton Comes to Harlem

Watermelon Man

The Big Doll House

Shaft

Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song

Super Fly

Buck and the Preacher

Blacula

Cool Breeze

Melinda

Slaughter

Hammer

Trouble Man

Hit Man

Black Gunn

Bone

Top of the Heap

Across 110th Street

The Legend of N***** Charley

Don’t Play Us Cheap

Shaft’s Big Score!

Non-Blaxploitation: Sounder and Lady Sings the Blues

Trick Baby

The Harder They Come

Black Mama, White Mama

This is definitely one where the soundtrack is better than the movie. James Brown's score is epically funky and soulful, and is one of his best albums. "The Boss", "Down and Out..." and "Mama's Dead" display his emotional rage as a singer, and he and Fred Wesley made some great instrumental tracks. And it's impossible to forget Lyn Collins charging through "Mama Feelgood".

(I suspect Brown might have taken the gig because he understood Tommy's story- he started his working life shining shoes in Augusta, Georgia before building up his (legitimate) music empire).