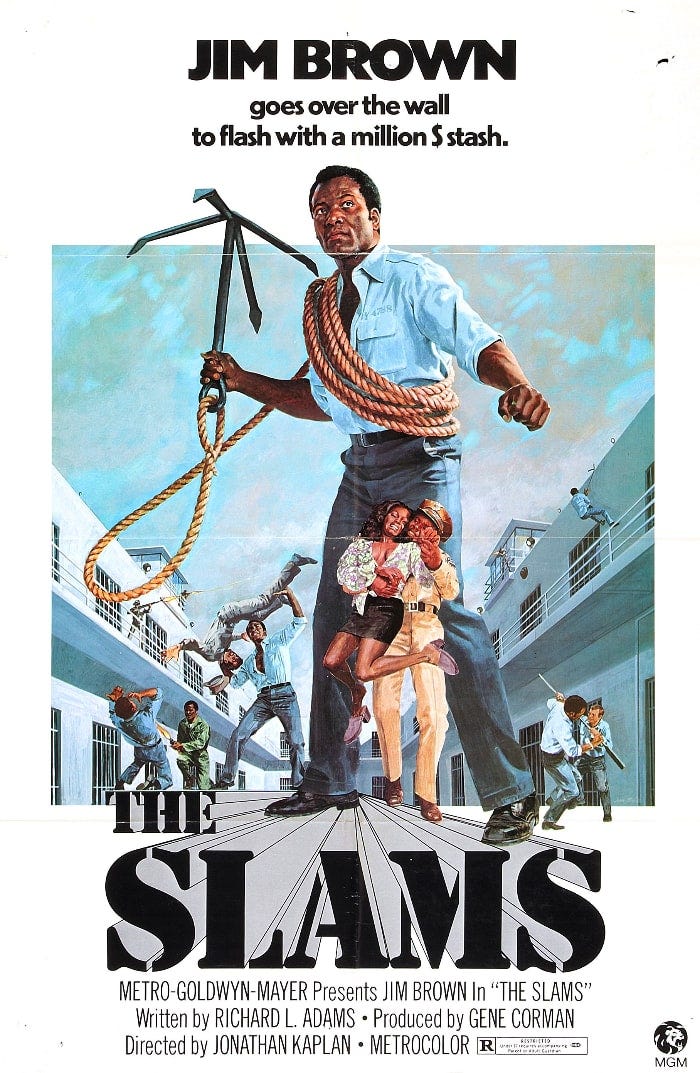

The Slams

Written by Richard L. Adams

Directed by Jonathan Kaplan

1973

As the Blaxploitation genre exploded in the 1970s, there were a few stars who rose to the stop, and of those, Jim Brown was not only one of the coolest, but also the one who arguably had the most staying power, given that he continued to be a recognizable name for the next several decades. It helped that he got a bit of a head start, first as an NFL player and then appearing in ensemble movies like The Dirty Dozen before becoming a movie-leading star in the late 1960s and early 1970s, just as the Blaxploitation era was getting started. But really, his ability to exude effortless cool while seeming believably tough enough to take on any challenger was what kept him on top.

There’s not a whole lot of variation in the types of characters Brown played, but that’s fine, because he’s good enough at it that many other lesser-known actors who led Blaxploitation movies could be described as “Jim Brown types.” He provides a non-showy center of gravity for any movie he’s in, rarely announcing his presence or provoking anyone, but always ready to stand up for himself and refusing to back down in the face of intimidation. And perhaps most crucially, he’s always ready to stand steadfastly in the face of any white authority figures who sling racial slurs at him in an attempt to try to provoke him into acting rashly. He doesn’t need to convince anyone that he’s superior to them; he just shows it through his actions.

In The Slams, Brown (making a rare moustache-less appearance) gets to take on one of the major institutions of Black oppression, and one that hadn’t been featured in the Blaxploitation genre very much at that point: prison. In the 70s, the system of mass incarceration in the United States was just getting started, but if this movie is any indication, Black people were already being put in jail at much higher rates than white people. While the movie doesn’t necessarily provide much in the way of insight into the injustices of the U.S. justice system, it does show that the system is hopelessly corrupt. Brown gets to mock the idea that the reason people are placed in prison is for rehabilitation, and it’s obvious that all of the authority figures, from the guards all the way up to the warden, are only involved in this system because they enjoy exerting authority over others and brutalizing them whenever possible.

The movie kicks off with a heist scene in which some mafia types are meeting in a remote location near some oil drilling equipment for a drug deal, but they taken out by a crew of robbers who abscond with both the money and the drugs. Jim Brown is Hook, one of the robbers, and while he doesn’t want to take the drugs, the others force him to do so. They’re both white guys who seem untrustworthy, and sure enough, they almost immediately turn on Hook and try to kill him. He anticipates this plan though, managing to shoot both of them first, but he takes a bullet in the leg and starts losing a lot of blood. With the last of his strength, he manages to hide the money (he dumps the drugs in the ocean), but he passes out while driving away, crashes their van, and gets arrested and thrown in prison.

Unfortunately, the story of what happened has preceded Hook, and everyone at the prison knows that he stole $1.5 million from “the syndicate.” This means that multiple parties have their sights set on him. Capiello (Frank DeKova), an older Italian prisoner who has enough power that he seems to run the joint from the inside, is ready to kill Hook, although he also acts friendly, thinking that maybe he can bribe Hook into telling him where the money is hidden. The leader of the prison’s Black faction, Macey (Frenchia Guizon), says that he has Hook’s back, but it’s clear that he’s also trying to get a piece of the money. And the head prison guard, Captain Stambell (Roland “Bob” Harris) is trying to exert authority against all sides while getting Hook to trust him, but he is also trying to lean on Hook’s girlfriend Iris (Judy Pace, who was in Cotton Comes to Harlem and Cool Breeze) and intimidate her into convincing Hook to split the money with him.

All of this forces Hook to negotiate an increasingly dangerous atmosphere. He tries to avoid getting caught up in the racial politics of the prison; when one guy calls him a racial slur, he laments that while Black and white prisoners are busy fighting with each other, they’re forgetting that they’re all being oppressed by The Man. But he can’t escape this violence completely, and he has to fend off several attacks by Capiello’s main enforcer, an intimidating guy named Glover (Ted Cassidy, who played Lurch in The Addams Family and makes for an especially despicable villain here as a large, angry man who is constantly slinging racial slurs). Hook does his best to navigate this brutal environment, but it seems like he’ll only be able to last so long before something will have to give.

That something turns out to be a news report about how the place where Hook hid the money (a kiosk at an abandoned amusement pier) is going to be demolished to make way for a new marina. If he doesn’t get out soon, the money is going to be discovered, and all of this will be for naught. So, he comes up with a plan to escape along with the help of his girlfriend and a pimp friend of his (Paul Harris, who was in Across 110th Street and The Mack), while also trying to play Capiello and Stambell against each other, creating chaos in the prison just as he’s in the midst of his escape. There are a few twists and turns, along with some nicely tense moments and scenes where various villains get their comeuppance, and as expected, Jim Brown ends up walking away victorious. Was there ever any doubt about whether that would happen?

As a B-movie that falls within the “prison escape” genre (it’s produced by Gene Corman, brother of king-of-exploitation Roger Corman), this provides some solid thrills, enjoyable action, and memorable characters. It does have a few questionable elements that are of-the-time, like the way various characters throw around the F-slur to refer to the homosexuals who are known to populate prisons. But it also provides at least a little bit of awareness of social issues, which should have been expected of pretty much any Blaxploitation movie by this point. It doesn’t fully go into commentary about how the prison system served (and has continued to serve) as a way to perpetuate the oppression of Black people in the post-civil-rights era, but it at least implies that Black people are treated unjustly by this system. That’s better than nothing. And really, simply depicting a Black man who is smarter, tougher, and more resourceful than everyone else around him is revolutionary enough. Giving Black audiences a hero they could admire and aspire to emulate is one of the best ways to poke racism in the eye, and few did that better than Jim Brown.

Blaxploitation Education index:

UpTight

Cotton Comes to Harlem

Watermelon Man

The Big Doll House

Shaft

Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song

Super Fly

Buck and the Preacher

Blacula

Cool Breeze

Melinda

Slaughter

Hammer

Trouble Man

Hit Man

Black Gunn

Bone

Top of the Heap

Across 110th Street

The Legend of N***** Charley

Don’t Play Us Cheap

Shaft’s Big Score!

Non-Blaxploitation: Sounder and Lady Sings the Blues

Trick Baby

The Harder They Come

Black Mama, White Mama

Black Caesar

The Mack

Book of Numbers

Charley One-Eye

Ganja & Hess

Savage!

Coffy

Shaft in Africa

Super Fly T.N.T.

Scream Blacula Scream

Cleopatra Jones

Terminal Island

Gordon’s War

Slaughter’s Big Rip-Off!

Detroit 9000

Hit!

The Spook Who Sat by the Door

Back to MGM land. Of all the major film studios, they must have made the most films in this genre.