Blaxploitation Education Extra: Charley One-Eye

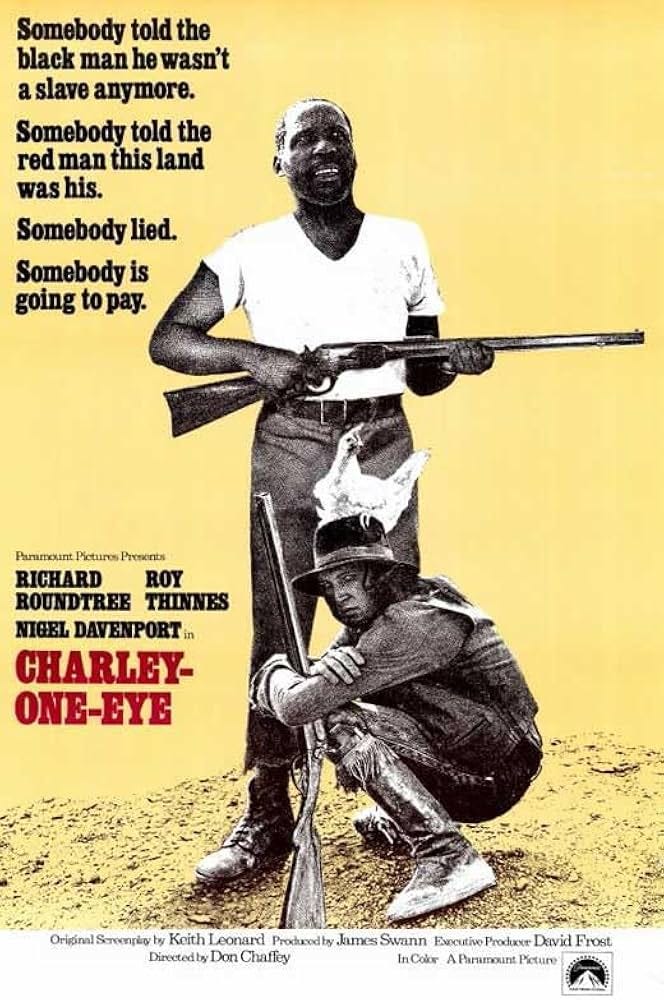

Richard Roundtree stars in a Western I probably shouldn't have bothered watching.

Usually, I use these “extra” posts to cover movies I watch that don’t really fit into the Blaxploitation genre. This time, I’m using it just because I didn’t like this one very much.

Charley One-Eye

Written by Keith Leonard

Directed by Don Chaffey

1973

As I proceed through this project, there are times when I’m probably going to question whether I should really try to watch everything that seems like it could be interesting, whether I’ve heard of it before or not. That approach has yielded some good results so far, including lesser-known gems like Book of Numbers and Trick Baby, but it has also turned up some that may be better forgotten, like Top of the Heap. And unfortunately, Charley One-Eye is one of the latter.

What we have here is a sort of Western, although it’s pretty limited in scope and has little in the way of action. It stars an almost-unrecognizable Richard Roundtree as a character known only as “the Black man,” and it’s possible that the filmmakers were going for a spaghetti-Western-style story about an antihero, because he’s a total asshole. As much as I wanted to root for him as a guy who was on the run and being hunted by a white bounty hunter, he sure makes it hard to do so.

We only get the briefest glimpses of backstory that let us know why Roundtree is on the run, including a moment of flashback in which a woman who appears to be the wife of a Union officer shoots a flirtatious glance toward Roundtree, one of the privates in the officer’s ranks. That’s all we need to see to realize that he has committed the unforgivable sin of sleeping with a white woman, so now he’s running on foot through a desert, with only a knife to defend himself.

That’s not a bad setup, but any goodwill that Roundtree has is almost immediately destroyed when he comes up on a sleeping Native American man. He wakes the guy up, threatens him, calls him a bunch of names, steals his food and water, and then decides the two of them are going to be traveling companions. This guy is only known as “the Indian,” and he’s played by Roy Thinnes, who is (as you can probably guess) not a Native American.

The idea here seems to be that the two characters will start off antagonistic but eventually become grudging allies, and yes, that’s what happens, but it’s hard to care all that much. Roundtree is a jerk throughout, always acting superior to Thinnes, even calling him “boy” in the same manner as racist white people used to refer to Black men in the past (and probably still do in certain parts of the United States, with that trend likely to get worse following the white supremacist takeover of our government). Perhaps he’s meant to be an example of how people who have been oppressed sometimes seek to oppress others in turn, but that certainly doesn’t make him any less unlikeable. And while he does eventually seem to come to an accord with Thinnes, there’s never really any redemption, so when he meets a tragic end, it’s not actually all that tragic.

As the movie proceeds, it’s basically just a series of events, some of which may be somewhat interesting, but they don’t seem to add up to very much. Roundtree and Thinnes come upon an old church, and they spend some time trying to figure out how to get water out of a well (after Thinnes does all the work, Roundtree grabs the first bucket of water and dumps it over his own head, cackling at how funny it is that he’s being an asshole like always). They find a dead guy who was transporting a cart containing some caged chickens and some guns, which is enough for them to set up shop at the church and live at least sort of comfortably for a while. They also have a confrontation with some Mexicans who are passing through and pulling a carriage that seems to be carrying money from a bank. Roundtree manages to get the drop on them and kills them both, but it turns out the carriage is empty.

Thinnes ends up adopting one of the chickens and treating it as a pet, calling it Charley One-Eye, so Roundtree naturally tries to kill it and eat it, leading to a tussle that only gets interrupted when the bounty hunter who has been tracking Roundtree catches up to them. This confrontation at least provides a sense of conflict that has some stakes, with the bounty hunter (Nigel Davenport) treating Roundtree not too dissimilarly from how he had been treating Thinnes, calling him racial slurs and inflicting violence when he’s not being deferential enough. Instead of taking Roundtree in and collecting the reward right away, he decides to take some time pleasuring in the pain he gets to inflict on a Black man, culminating in a whipping. But when he tries to get Thinnes to participate, this becomes too much, and Thinnes ends up turning on the bounty hunter, killing him, and rescuing Roundtree.

While this might signal some newfound respect between the two characters, it doesn’t last long, since a bunch of Mexicans show up to get revenge for the guys who were killed earlier. They execute Roundtree through the unconventional method of stoning, and when Thinnes discovers what happened, he’s upset enough to kill all of their remaining chickens in the final shots of the movie. Maybe that’s meant to signify something, but I couldn’t tell you what. It probably just seemed like a dramatic series of images to end things on.

Maybe this is meant to be one of those 1970s movies that were total downers, with morally compromised characters making questionable decisions and meeting meaningless ends. But I do kind of question whether that was the intent, since the director, Don Chaffey, wasn’t exactly known for that sort of thing, with his previous movies being cheesy sci-fi or fantasy films like One Million Years B.C. and Jason and the Argonauts. He did also direct episodes of the British TV series The Avengers and The Prisoner, so he must have had some artistic sensibilities. But outside of some occasional bits of nice editing, that’s not very evident here.

As an attempt at a spaghetti Western, this lacks the epic scope, exciting action, or interesting character work that made the best of those movies work so well. It also fails as an examination of a Black character trying to make his way in a hostile world (Roundtree notes that he was happy to be a Union soldier, since it meant he got to get paid to kill white people, but he also laments that the same people who paid him wanted to string him up for killing the wrong white person), since the character is so unlikeable that we don’t really care whether he survives or not. And it fails once again as a buddy picture about antagonistic characters building a relationship, since Thinnes is far too willing to get over Roundtree’s awful treatment of him and act like they’ve been longtime friends. The movie is a trifecta of unsatisfaction, and one that I’ll be glad to forget along with the rest of the world.

Blaxploitation Education index:

UpTight

Cotton Comes to Harlem

Watermelon Man

The Big Doll House

Shaft

Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song

Super Fly

Buck and the Preacher

Blacula

Cool Breeze

Melinda

Slaughter

Hammer

Trouble Man

Hit Man

Black Gunn

Bone

Top of the Heap

Across 110th Street

The Legend of N***** Charley

Don’t Play Us Cheap

Shaft’s Big Score!

Non-Blaxploitation: Sounder and Lady Sings the Blues

Trick Baby

The Harder They Come

Black Mama, White Mama

Black Caesar

The Mack

Book of Numbers