I’ve been reading Black Caesars and Foxy Cleopatras: A History of Blaxploitation Cinema by Odie Henderson, and it’s got plenty of fascinating information about films from that era, which stretched from the late 60s to the end of the 70s. I’ve seen a few of those movies, but my experience is by no means comprehensive, so this seems like a good opportunity to expand my knowledge of the genre and delve into what made these films so interesting. Let’s start with:

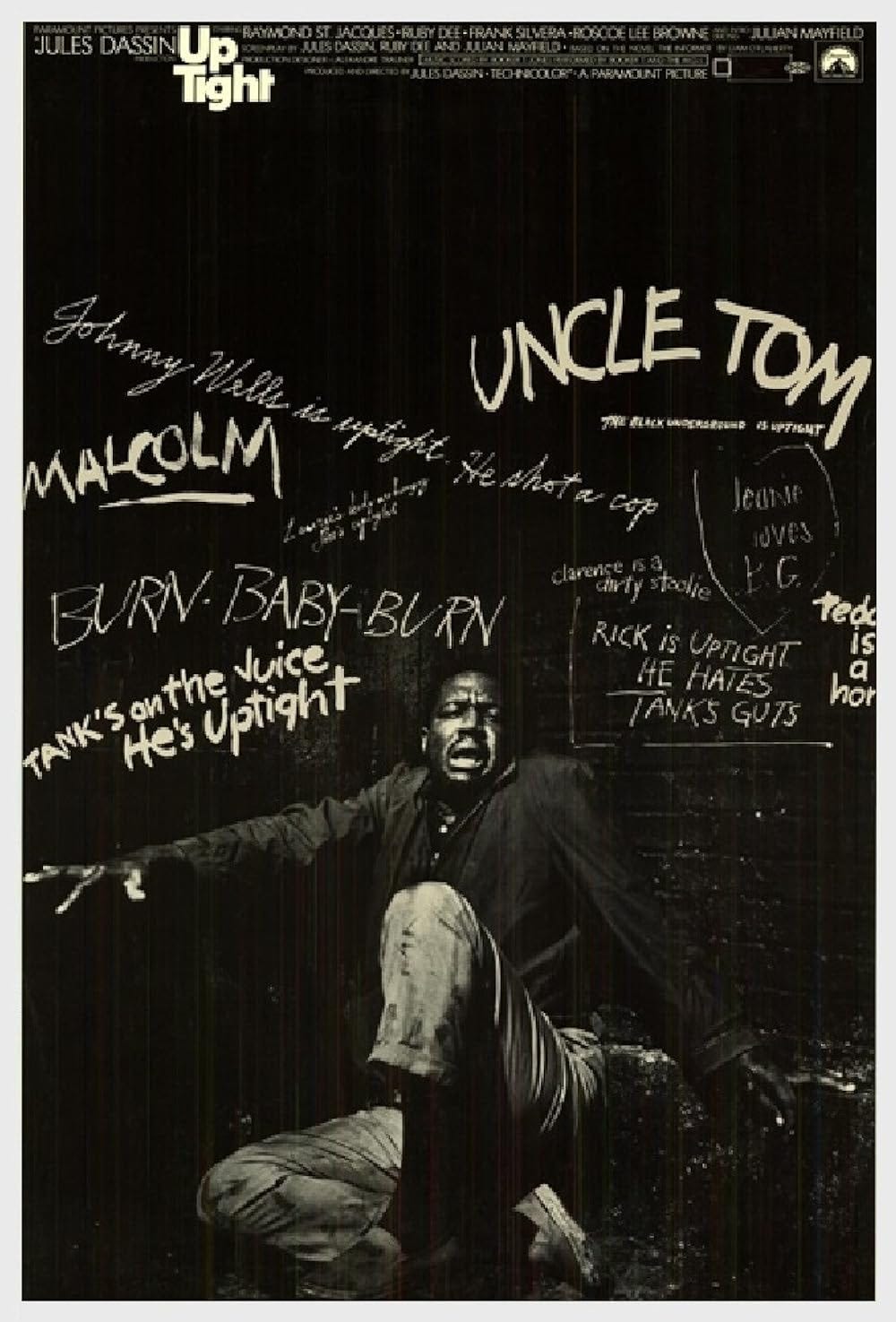

UpTight

Directed by Jules Dassin

Written by Jules Dassin, Ruby Dee, and Julian Mayfield

1968

Henderson argues that this is the first Blaxploitation movie, although it seems to me to be more like a precursor to a genre that would develop its own styles and rhythms. It was released in 1968, soon after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., and it has a feeling of rawness and anger, with Black revolutionaries who have been fighting for freedom and equality starting to feel like no matter what they do, the white man will always seek to subjugate them and punish them for trying to overcome oppression. In fact, the movie opens with footage from MLK’s funeral, giving us a look at the sadness and anger that so many people felt in the aftermath of this unspeakable act of violence against a man who sought to find peaceful solutions to the horrors his community had been experiencing for centuries.

The rest of the movie doesn’t quite live up to that opening, possibly because it had to incorporate real-world events at a late stage in production. Instead, it focuses on the personal plight of one man who has been broken down and acts out of desperation. That would be a guy named Tank, played by Julian Mayfield, who is barely hanging on after struggling to maintain employment, spending most of his time drinking. He refuses to join his friend Johnny (Max Julien) in a robbery of weapons that will be used by a Black revolutionary group, and when Johnny kills a night watchman, he ends up being the focus of a manhunt by the Cleveland police.

We get some scenes in which different factions of Black revolutionaries discuss their tactics, although there’s little in the way of concrete plans and more of a suggestion that they are ready to use violence. One local leader, who wants to work within the system to effect change, advocates for peaceful solutions, but he gets overruled by the younger leaders who have had enough of oppression. However, we don’t really see these people do much of anything except deal with the Johnny situation. Instead, the focus is on Tank, who wants to clean himself up and become involved in the movement, but gets rejected due to his general unreliability and drunkenness.

At the end of his rope, Tank ends up giving Johnny up to the police, leading them to hunt him down and kill him when he tries to flee. This sends Tank on a spiral of debauchery as he uses the reward money to go on a bender, buy drinks for people at a series of bars, donate to charity, and eventually show up at Johnny’s wake in a fit of sorrow and guilt. When the revolutionary leaders become suspicious about where he got the money and why he’s so worked up, you know he’s not long for this world.

So, as much as the movie purports to be about the struggles of the Black community, it ends up being a near-phantasmagorical journey through one guy’s anguish at being unable to survive in a hostile world. Unfortunately, Mayfield doesn’t quite have the acting chops to sell the emotional breakdown he’s supposed to portray. He spends most of the movie with a sheen of sweat on his face and expressions of anguish and desperation. He alternates between manic giddiness and extreme sadness, giving an extra-large performance that’s well past the point of believability.

Some of this may just be chalked up to the acting style of the time, but there are other members of the cast who handle extreme emotions much better, including a devastating scene in which Tank’s sometime lover, played by Ruby Dee, devolves into a fit of anger after she learns what he did, slapping and scratching him as she wails in sadness and anguish. That’s a much more powerful moment than most any of Tank’s over-the-top emotions.

The other interesting aspect of the film is the style that director Jules Dassin brings. It opens with some gorgeous animation under the credits, full of ink splotches and flowing movement depicting Tank and Johnny’s long-time relationship from their childhood to the present. The camera spins disorientingly at the moment of Johnny’s death, selling the horror and tragedy of the scene. There’s also a strange scene in which Tank is approached by a bunch of white dilettantes while playing games at an arcade. When they quiz him about the plans of the Black revolution, he makes up a bunch of nonsense, and the conversation is depicted as a reflection in a funhouse mirror, distorting everyone’s heads and bodies and making the whole thing especially ridiculous.

Overall, this is an interesting start to what would become a movement that focused on depicting Black people as more than just supporting characters or stereotypical comic relief. As I watch more of these movies, I’ll be curious about whether the pattern established in this movie will be repeated, with characters talking about larger issues that affect the Black community but the focus being on individual characters. I know some later movies received some criticism for negative portrayals that could encourage stereotypes, fear, and divisiveness. However, they also provided some examples of Black people overcoming oppression, standing up against the white man, and achieving victories. I’m definitely excited to see how the genre develops.

This film is based to a degree on a 1930s film, "The Informer", about an Irish man accused of "selling out" to the British. Victor McLaglen won an Oscar playing the title character, Gypo Nolan.